Chapter 1. The Simplicity of the Economy

At first glance, the economy seems impossibly complex. Millions of people, billions of transactions, countless products and services moving around the globe every day. Yet beneath the surface, the logic of the economy is remarkably simple. It is built on one timeless structure: the contract.

A contract, whether formal or informal, is an agreement between parties. It specifies rights and obligations: who delivers, who pays, under what conditions, and by when. Once these conditions are fulfilled, the contract is complete. This pattern repeats everywhere. From buying a cup of coffee to financing an aircraft, the structure is the same.

The power of contracts lies in their declarative nature. They do not dictate the precise steps each party must take. Instead, they define the what and leave the how to the parties themselves. If you agree to deliver a product, it is your responsibility to figure out shipping, packaging, and timing. The contract only cares whether the product arrives as agreed. This separation between declaration and execution is what makes contracts both flexible and scalable.

History offers us a striking reminder of this simplicity in the form of double-entry bookkeeping. Invented centuries ago, it provided a systematic way of recording the obligations created and fulfilled by contracts. With nothing more than two columns - debits and credits - merchants could track who owed what to whom. It was the first true “digital” system in the sense that it abstracted away the messiness of individual transactions and reduced them to a consistent, verifiable record.

Seen in this light, the economy is not a chaotic web of activity but a highly structured network of contracts and their execution. The complexity we experience is often the byproduct of the scale of interactions, not of the logic itself. Each new contract is simply another instance of the same pattern.

This simplicity is both profound and instructive. It suggests that if our digital systems mirrored the declarative, contract-based nature of the economy, they too could remain simple even as they scale. Yet, as we will see in the next chapter, that is not the path enterprise IT has taken. Instead, we modeled contracts with tools designed for something very different: messages and APIs. And in doing so, we imported accidental complexity into the heart of our digital infrastructure.

Chapter 2. The IT Shortcut: Messaging and APIs

When enterprises first began digitizing their operations, they faced a practical challenge: how to make different systems talk to each other. Finance needed to send data to logistics. Logistics needed to notify sales. Sales needed to trigger invoicing. The tools available at the time were databases, message queues, and later, APIs. It was natural to reach for these.

At a small scale, the approach worked. A message could signal that a shipment had left the warehouse. An API call could confirm a payment had been received. Each connection was a modest technical bridge between two processes. Taken in isolation, these bridges were simple enough to design and maintain.

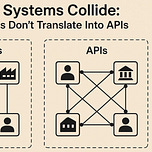

But step back and notice what happened: instead of modeling the contract that bound the parties together, IT modeled the steps that each system needed to take. The economic reality was declarative - “deliver the goods, pay the invoice” - yet the technical solution was procedural - “call this API, then send that message, then update this record.”

This shift had subtle but far-reaching consequences.

First, it hardwired dependencies. If one system failed to respond to an API call, the entire flow could stall. If a message was lost in transit, reconciliation was needed. The declarative independence of contracts gave way to brittle chains of interdependent calls.

Second, it fragmented state. Each system kept its own record of what had happened. Was the invoice paid? Sales thought yes, finance thought no, and logistics was waiting for confirmation. Instead of one shared contract state, there were many partial states scattered across databases.

Third, it locked us into procedure. Every interaction required agreement not only on what was to happen but on how it should be executed step by step. This demanded custom integration logic for every pair of systems, making change slow and costly.

To be fair, APIs and messaging were the best tools available at the time. They solved the immediate problem of connecting disparate systems. Without them, large-scale automation would never have been possible. But they were also a shortcut. Rather than reflecting the declarative logic of the economy, they imposed a procedural model that worked against it.

The cost of this shortcut was not immediately obvious. Early projects were manageable. But as connections multiplied, the burden grew. What started as a convenient way to wire systems together became the foundation for an architecture whose complexity only increases with scale.

In the next chapter, we will explore the consequences of this design choice. What does it mean when millions of contracts are modeled not as agreements but as chains of procedural calls? The answer is the overwhelming complexity we now take for granted in modern enterprise systems.

Chapter 3. The Complexity Explosion

At some point, the procedural shortcut taken by IT stopped being convenient and started becoming overwhelming. What was once a neat set of integrations turned into sprawling networks of connections, dependencies, and reconciliation layers. The simplicity of the underlying economy - contracts and their fulfillment - became buried under mountains of technical complexity.

Why did this happen? Several forces converged:

1. Fragmented state

Every contract has a lifecycle: it is initiated, executed, and completed. In a contract-based world, this lifecycle is singular - all participants refer to the same agreement. In a messaging/API world, however, each system maintains its own partial record. Finance keeps a ledger, logistics keeps a delivery database, sales keeps a CRM entry. If any one of these records diverges, someone has to resolve the mismatch. Multiply this across thousands of contracts, and entire teams are employed just to reconcile differences.

2. Tight coupling

Contracts allow each party to manage its own obligations independently. By contrast, APIs force one system to depend directly on another’s availability and design. If the supplier changes their interface, the buyer must adjust their code. If a payment service is temporarily down, the entire chain can grind to a halt. Instead of independent autonomy, we end up with fragile interdependencies.

3. Procedural rigidity

A contract declares what must happen; how it happens is left open. Messaging and APIs reverse this: they prescribe the how in detail. The sequence of calls, the payload structures, the timing of acknowledgments - all must be agreed upon in advance. This rigidity makes systems difficult to adapt when business conditions change, because changing the business logic requires rewriting technical procedures.

4. Reconciliation as a permanent industry

Every time messages are lost, delayed, or misinterpreted, states diverge. Banks, supply chains, insurers - all spend heavily on reconciliation teams and tools. Clearinghouses, auditors, and middleware platforms exist largely to cope with the errors that stem from the mismatch between declarative contracts and procedural IT. What should be a simple verification of obligations becomes a costly, ongoing battle to restore a shared view of reality.

5. Scaling beyond reason

Perhaps the most insidious force is scale. With messaging and APIs, every new participant requires explicit connections to many others. If there are N participants, there are potentially N² integrations. At small scales, this is manageable. At the scale of global commerce, it becomes impossible without layers of brokers, hubs, and middleware - each of which adds more complexity and fragility.

The irony is striking: the economy itself scales beautifully. Adding another buyer, supplier, or bank is straightforward because contracts remain local and declarative. Yet our digital infrastructures scale poorly because they are built on procedural glue. The result is a system where most of the cost and risk lies not in the business activity itself, but in the effort to keep digital records aligned with reality.

This is why enterprises today carry vast technical debt. It is not only the result of outdated software or legacy systems; it is the structural outcome of having modeled a declarative economy with procedural tools. The complexity we live with is not inevitable. It is the byproduct of a mismatch.

In the next chapter, we will illustrate this mismatch with a simple example: a purchase order involving a buyer, a supplier, and a bank. By comparing the API/messaging approach with a contract-based approach, the contrast will become clear. What appears overwhelmingly complex in one model is disarmingly straightforward in the other.

Chapter 4. A Tale of Two Models

To make the contrast clear, let’s walk through a simple scenario: a buyer places a purchase order with a supplier, and the payment is financed by the buyer’s bank. Three parties, one transaction.

At the level of economic reality, this is straightforward.

The buyer agrees to purchase goods.

The supplier agrees to deliver them.

The bank agrees to release funds once delivery is confirmed.

The contract defines rights and obligations. Once those are met, the transaction is complete.

Now let’s see what happens when we model the same scenario in two different ways.

The API/Messaging Model

In the procedural world of IT, this transaction quickly becomes a web of calls and updates:

The buyer’s system sends a purchase order message to the supplier’s system.

The supplier’s system acknowledges receipt.

The supplier checks inventory and sends back an order confirmation.

The buyer’s system updates its records and notifies the bank.

The bank requests proof of the order from the supplier.

The supplier responds with shipping data.

The bank confirms the data and authorizes funds.

The buyer’s system updates payment status.

The supplier’s system updates delivery status.

Each step involves a message or API call, error handling, retries, and database updates. If one call fails, reconciliation is required. If two systems disagree, humans step in. With three parties, this is already cumbersome. With a larger number of parties, it eventually becomes unmanageable.

The Contract-Based Model

In a contract-based system, the same transaction is modeled as a single shared contract:

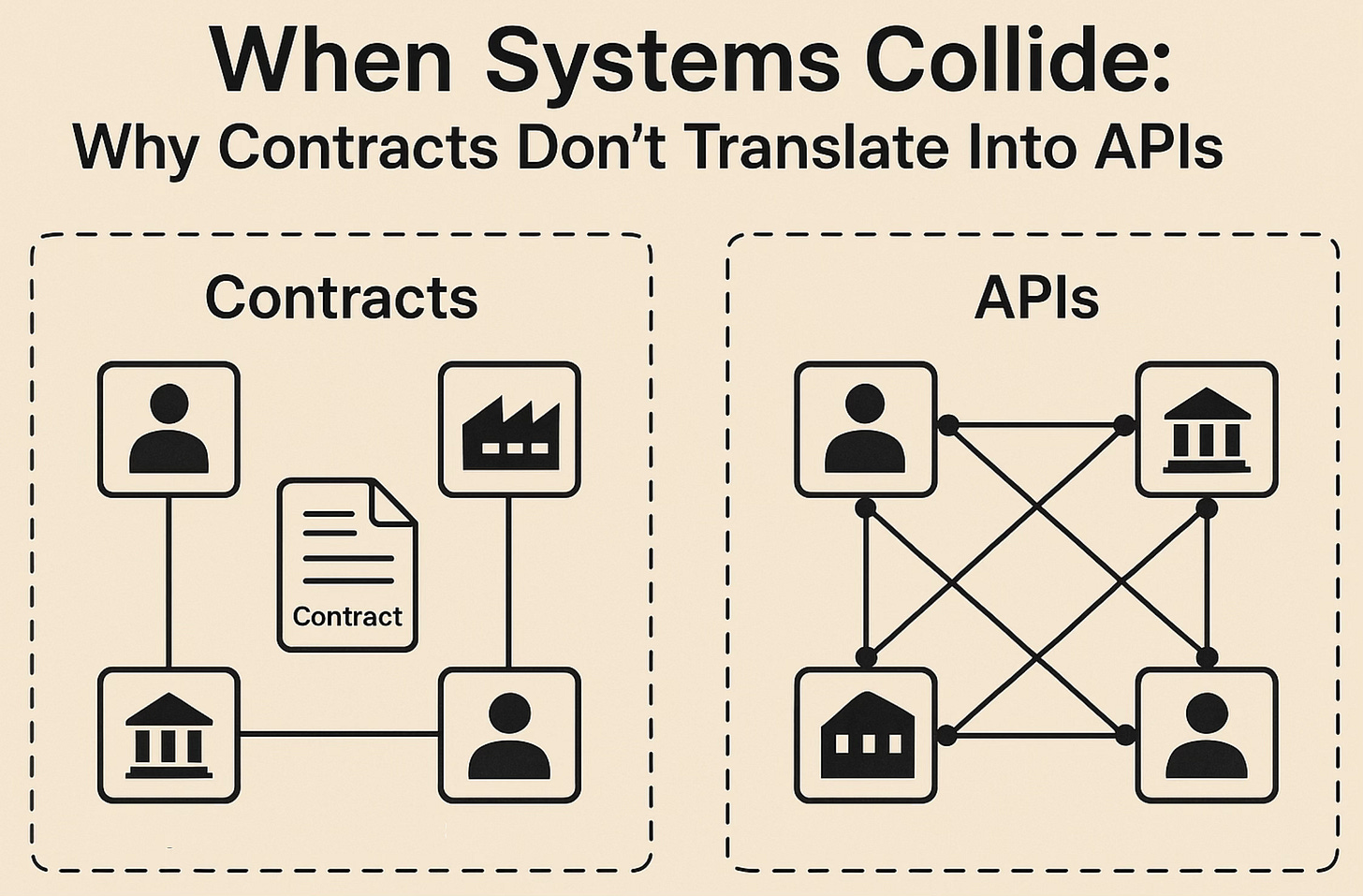

The buyer, supplier, and bank agree on the contract terms: goods to be delivered, payment conditions, and financing arrangements.

Each party signs the contract digitally, committing to their obligations.

As delivery and payment occur, each party issues verifiable claims (for example, “goods delivered,” “funds reserved,” “payment executed”).

The contract agent evaluates the claims against the contract terms and finalizes the outcome.

That’s it. There are no scattered calls, no procedural chains. Each party manages its own obligations, and the contract itself provides the single source of truth.

The Difference in Practice

In the API/messaging model, the logic of the transaction is spread across systems. State is fragmented, errors are inevitable, and reconciliation becomes permanent work.

In the contract model, the logic of the transaction lives in the contract itself. State is unified, obligations are clear, and reconciliation is built-in. Each party can verify for itself that the contract was executed as agreed.

The difference might appear subtle at first, but it compounds dramatically at scale. Multiply the purchase order example by thousands of buyers, suppliers, and banks, and the API/messaging model creates exponential complexity. The contract model, by contrast, simply adds more instances of the same pattern.

This is the heart of the matter: one model scales against the economy, the other scales with it.

In the final chapter, we will look at what it means to return to contracts as the digital primitive - and why doing so might be the only way to escape the complexity trap we have built for ourselves.

Chapter 5. Returning to Contracts as the Digital Primitive

If the root cause of our complexity is the mismatch between declarative contracts and procedural IT, the path forward is clear: we must return to contracts as the digital primitive. Instead of mimicking agreements with chains of API calls and messages, we should make agreements themselves the first-class citizens of our digital infrastructure.

What would this look like in practice?

1. Contracts define, not procedures.

Rather than prescribing how systems must call each other, a digital contract declares the obligations of each party. The execution of those obligations remains local, but their fulfillment can be verified universally.

2. Each party manages its own obligations.

In a contract-based architecture, there is no need for one system to reach deep into another to trigger a process. Each participant issues verifiable claims about what they have done, and those claims form the evidence of execution. Autonomy is preserved, and coupling is avoided.

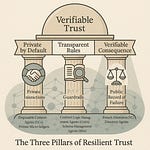

3. A single source of truth.

Instead of scattered databases and fragmented state, the contract itself becomes the shared record of the transaction. Each participant can rely on it without requiring reconciliation layers, because it is verifiable by design.

4. Simplicity at scale.

When the unit of transaction is a contract, scaling is straightforward. Adding more participants does not multiply integrations; it simply means more contracts. Complexity grows linearly, not exponentially. The architecture mirrors the scalability of the economy itself.

5. A foundation for trust.

Most importantly, contracts are how trust is already managed in the real world. By digitizing them faithfully, we align technology with law, commerce, and human expectation. This creates a foundation where financial institutions, enterprises, and individuals can transact in real time without inheriting the accidental complexity of legacy IT.

The implications are significant. Entire industries built around reconciliation, clearing, and middleware could be simplified and even made obsolete. Financial transactions could settle instantly, supply chains could coordinate seamlessly, and regulatory compliance could become a natural output of verifiable contracts rather than an afterthought.

None of this requires reinventing the economy - it requires aligning our digital systems with the way the economy already works. We need to recognize that complexity is not inevitable but optional, and that we have the tools to choose differently.

The story of IT has been one of constant patching, reconciling, and integrating. Perhaps the next chapter can be different. If we take contracts as the starting point rather than the afterthought, we can build systems that are not only more efficient, but more faithful to the economic reality they are meant to serve.