1. The Trouble with Ecosystems

The word ecosystem has become one of the most overused and least examined terms in the vocabulary of digital trust. It appears in presentations, policy papers, and standards documents as if everyone already agrees on what it means. Yet the moment you ask how one actually becomes part of an ecosystem, the answers turn vague. Some point to governance frameworks. Others refer to registries of approved issuers. Many simply equate the term with “a community of participants who trust each other.”

The problem begins with good intentions. When early identity federations emerged, they required a central operator to maintain lists of trusted domains and rules for how they could interact. That model was later generalized into what the SSI community started to call trust ecosystems. It was a familiar and comforting concept — an extension of federation into the world of verifiable credentials. If organizations could agree on a set of rules, a list of trusted issuers, and a shared directory, they would, in theory, create a digital environment where everyone could rely on each other’s credentials.

This approach worked well as long as participation remained small and centralized. But as soon as decentralization entered the picture, the metaphor began to break down. A true digital trust network cannot rely on anyone maintaining a master list. It cannot depend on a single governance authority to decide who is allowed to issue what. Nor can it require prior membership before interaction, because that would reintroduce the very bottlenecks decentralization was meant to remove.

In practice, the ecosystem model has often re-centralized the systems it sought to free. The registry becomes a gatekeeper. The governance body becomes an arbiter. And the notion of “membership” returns under a new name, shaping who can participate and how. What looks decentralized on paper still behaves like a federation in disguise.

The deeper issue is conceptual. If we remove the membership list, what remains of an ecosystem? What does it mean to belong in a network where trust is derived from cryptography, not approval? If each participant carries its own root of trust, how can anyone recognize another as part of the same whole?

This is where the term ecosystem reveals its ambiguity. It has always been borrowed from biology, where it describes a system of interdependent organisms sharing an environment. But in digital trust, there is no shared environment—only shared meaning. The integrity of an interaction depends not on who you are connected to, but on whether the data you exchange and the logic you follow can be verified as consistent.

In that sense, the idea of a digital ecosystem is less about membership and more about mutual intelligibility. Two agents can cooperate the moment they understand and verify each other’s claims using a common schema and a common set of contractual rules. The ability to communicate verifiably is what creates belonging.

This observation leads to a much simpler and more precise definition: perhaps ecosystems are not organizations at all, but languages.

They emerge wherever participants use compatible vocabularies and grammars of interaction — schemas that define what is said, and contract logic that defines how it is understood and acted upon.

If we accept this shift, then the task of building ecosystems changes completely. It is no longer about managing memberships or registries; it is about defining and maintaining shared meaning. That is the perspective from which the Internet Trust Layer begins.

2. Where the Idea Came From

The need to identify, verify, and transact across digital boundaries is as old as the internet itself. In the beginning, identity was local: every service created its own usernames and passwords. Then came federation—an attempt to link those islands through shared directories and single sign-on. Federation made digital identity manageable within defined communities, but it also made trust conditional on inclusion. To be recognized, one had to be listed.

When the Self-Sovereign Identity (SSI) movement emerged, it promised to dissolve those dependencies. Trust, it argued, should no longer depend on central authorities or administrative lists, but on cryptographic proofs. Individuals and organizations could issue and verify credentials directly, without an intermediary keeping score.

It was an inspiring vision, but not a complete one. Even as new technologies—DIDs, verifiable credentials, decentralized identifiers—took shape, the social structure around them remained curiously familiar. The same actors who once managed federations began designing ecosystems to govern decentralized credentials. They established governance frameworks, trust registries, and membership models that looked remarkably like the federated systems they sought to replace.

The intention was sound: to create order, interoperability, and accountability. Yet the effect was to rebuild the same hierarchy, only with different vocabulary. The technology was decentralized, but the trust model was not.

That paradox led to a simple realization: decentralization cannot be achieved by redistributing authority; it must be achieved by redefining what authority means.

In the Internet Trust Layer (ITL), authority is not granted by a registry or a governance framework. It is derived from verifiable language—from the ability of two agents to exchange data and execute contracts that both can prove to be authentic and consistent. Trust does not flow from belonging to the same ecosystem; it flows from using the same semantics.

This way of thinking borrows less from institutional design and more from communication theory.

In human interaction, we don’t need to belong to a club to converse meaningfully. We only need to share a language. The same principle applies in digital trust networks. When two agents share compatible schemas and contract logic, they can interact verifiably, no matter who they are or where they come from.

This idea reframes the entire purpose of what the SSI community calls an ecosystem. Instead of organizing participants under a single governance framework, ITL organizes meaning under a set of verifiable definitions. Schema Management Agents define the vocabulary. Contract Logic Management Agents define the grammar. When an agent commits to use those definitions, it effectively learns a new language — and by doing so, joins the ecosystem that speaks it.

Seen this way, digital ecosystems cease to be federations and become semantic environments: dynamic, overlapping domains of shared understanding. They are not maintained through governance documents or member registries, but through the living links of trust that connect participants to the schemas and logic they choose to follow.

This is where the linguistic model of ITL was born. It did not arise from a need to manage participation, but from the realization that digital collaboration already behaves linguistically. Every transaction is an act of communication. Every verifiable credential is a statement that must be understood in context. And every contract is a grammar rule that gives meaning to data and intent.

When you build a trust network that recognizes this structure, you no longer need to decide who belongs. The network itself knows, because meaning is what defines membership.

3. Trust Without Membership

For as long as institutions have existed, trust has been managed through membership. We have trusted what is inside the boundary — the certified professional, the licensed bank, the registered supplier — and treated everything outside with caution. Membership has always been a proxy for trust, a signal that someone has been verified by an authority.

That model made sense in a world of paper and proximity. Verification was slow, expensive, and often manual. Institutions emerged to manage it at scale. They maintained ledgers, registries, and rules. To participate, you had to be enrolled. Once enrolled, you were trusted — not because of your behavior, but because of your inclusion.

Decentralization changes that equation completely.

When every participant can present verifiable proofs of identity, credentials, and contractual performance, the logic of membership becomes redundant. Trust no longer depends on being inside someone else’s circle. It depends on your ability to demonstrate facts that others can verify directly.

This is the shift that the Internet Trust Layer formalizes.

In ITL, trust is not inherited or acquired; it is performed. Each transaction creates the conditions for trust through a sequence of verifiable interactions between agents. The process is symmetrical: every participant verifies and is verified in return.

To illustrate, imagine two agents meeting for the first time.

Neither has been pre-approved or registered in the other’s domain. Yet both hold verifiable credentials and use compatible schemas and contract logic. They can prove who they are, confirm the integrity of their data, and execute a contract whose rules are explicit and machine-verifiable. At no point do they require a common administrator. Their ability to transact is established not through prior membership, but through immediate, verifiable understanding.

This model mirrors how trust functions in real human interaction.

We don’t verify each other by consulting a registry before speaking. We rely on shared language, recognizable behavior, and the capacity to make and keep promises. Over time, that interaction builds reputation — another form of verifiable evidence. In ITL, these dynamics are digitized: every credential, contract, and transaction becomes part of an agent’s verifiable history, accessible when needed, private when not.

The crucial insight is that membership and trust are not the same thing.

Membership is administrative; trust is relational. Membership is static; trust is continuously produced. And membership is exclusive, whereas trust — when built on verifiable evidence — is inclusive by design.

By removing the need for pre-approved membership, ITL reclaims the fluidity that real commerce and cooperation require. Agents can enter, transact, and depart without bureaucratic friction. They can operate across industries, geographies, and regulatory environments as long as the schemas and contract logic they adopt are recognized and verifiable.

This also resolves the scalability problem that has limited previous trust frameworks.

When trust depends on registries, it grows linearly with administrative effort. When trust depends on verification, it grows exponentially with participation. Every new interaction strengthens the overall trust fabric, adding new proofs and contexts that others can reuse.

In this sense, ITL reverses the old order.

Instead of joining to trust, participants now trust to join.

They don’t wait to be accepted into an ecosystem; they create it by expressing verifiable intent and following a shared business language. The boundary of the ecosystem isn’t drawn by policy — it’s drawn by comprehension.

When membership is replaced by understanding, the digital economy begins to behave like the real one. People and organizations collaborate not because someone permits them to, but because they can verify that what they share is true.

That is trust without membership — and it’s the foundation upon which the Internet Trust Layer is built.

4. Ecosystems as Shared Business Languages

If membership is no longer the organizing principle of digital trust, what takes its place?

In the Internet Trust Layer, the answer is both simple and powerful: shared meaning.

An ecosystem, properly understood, is a community of comprehension. It exists wherever a set of participants can exchange data and execute contracts using the same definitions and the same logic — where the information exchanged between them means the same thing to everyone involved.

This is why the most natural way to describe an ecosystem is as a language.

Every language has two essential elements: vocabulary and grammar. Vocabulary provides the words — the building blocks of expression. Grammar provides the rules that give those words structure and meaning. Without both, there is no understanding; without understanding, there is no trust.

The Internet Trust Layer formalizes this linguistic structure through two specialized types of agents:

Schema Management Agents (SMAs) define and publish the vocabulary — the verifiable data and credential schemas that describe the objects of interaction.

They define what a “Payment Order,” “Shipment Notice,” or “Identity Assertion” actually means in verifiable data terms.

Each schema is published as a signed, versioned artifact that any agent can reference and verify.

Contract Logic Management Agents (CLMAs) define and publish the grammar — the executable rules and contract logic that specify how those data elements interact.

They define how payments are settled, how shipments are confirmed, or how agreements are finalized.

Contract logic is likewise published in verifiable, versioned form.

Together, these two layers — schema and logic — form what ITL calls a business language.

When a node (a Person Agent or Contract Agent) wishes to participate in a particular business context, it establishes verifiable trust links to the Schema Management Agent(s) and Contract Logic Management Agent(s) that define that language.

This act of linking is the digital equivalent of learning to speak a new language: it signals the agent’s ability and intention to communicate according to those definitions and rules.

At that moment, the agent becomes part of an ecosystem — not by joining a list, but by adopting a language. Its commitment is verifiable, explicit, and dynamic. It may last for the duration of a single transaction or continue indefinitely as long as the agent keeps using the same schemas and logic.

This model also captures how ecosystems evolve.

When the underlying schema or logic changes, a new “dialect” emerges. Some participants may migrate immediately, others may stay with the old version, and both remain verifiable. No coordination or re-registration is required — the trust links themselves describe who speaks which dialect.

Just as languages can coexist and overlap, so can ecosystems.

A logistics company may operate in both a Shipping ecosystem and a Financing ecosystem, using different schemas and logic for each. In fact, a single agent can “speak” multiple business languages simultaneously, forming bridges between domains. This is how interoperability in ITL naturally arises — not through centralized governance, but through multilingual participation.

Because ecosystems are defined by language, not by authority, they are inherently decentralized. The Schema and Contract Logic Management Agents do not control who can participate; they only publish definitions that others may choose to use. Authority shifts from institutional control to semantic precision — from governance of people to governance of meaning.

And meaning, once verifiable, becomes the most powerful form of trust there is.

In this way, ecosystems in ITL are not administrative structures but semantic environments. They emerge wherever participants share a verifiable vocabulary and grammar for interaction. They are self-forming, self-verifying, and self-evolving. The network doesn’t decide who belongs; comprehension does.

Understanding replaces admission. Shared language replaces membership. And trust, once again, becomes a function of understanding.

5. The Role of Directory Agents

A language, no matter how well defined, is of little use if no one knows who speaks it.

In the Internet Trust Layer, understanding begins with semantics, but collaboration begins with discoverability. That is the role of Directory Agents — to make the speakers of a shared business language visible to one another without creating a central point of control.

Directory Agents form the discovery and trust publication layer of the network. They are the connective tissue that turns individual commitments into living ecosystems. When an agent establishes trust links to certain schemas and contract logic, it may also choose to publish its verifiable metadata to one or more Directory Agents. This act signals: I speak this language, and I can be reached through this channel.

By doing so, the agent establishes its presence within that ecosystem.

Other participants using the same language — that is, those who trust the same schema and logic definitions — can query Directory Agents to discover compatible peers. The directories, in turn, do not decide who qualifies. They merely relay verifiable information about who has declared adherence to what.

In practice, this creates a distributed, self-organizing discovery fabric.

Each Directory Agent maintains verifiable records of the agents it serves, including their DIDs, the schemas and logic they reference, and any additional metadata they choose to expose. Directory Agents relay this information across the network so that discovery is not limited by geography or institution.

Importantly, not all directories are equal — nor should they be.

Some will specialize in specific industries or regulatory domains. Others will serve as general-purpose discovery hubs. Ecosystem participants will naturally converge around certain directories that are widely used and well maintained, much like speakers of a language tend to gather where conversation is active.

In ITL, a node’s participation in an ecosystem therefore has two complementary dimensions:

Semantic commitment — expressed through trust links to Schema and Contract Logic Management Agents; and

Topological presence — expressed by publishing verifiable metadata to at least one Directory Agent widely used by other members of that ecosystem.

These two dimensions together make the ecosystem both intelligible and visible.

The first ensures that agents understand each other; the second ensures that they can find each other.

Unlike traditional registries, Directory Agents are not authorities. They don’t grant trust, approve membership, or mediate interactions. They simply provide a verifiable channel for discovery. Their role is infrastructural, not institutional. Any agent can become a Directory Agent by offering discovery services and earning trust through performance and transparency.

This approach preserves the autonomy of every participant.

Each node decides which directories to trust ant use, which ecosystems to publish into, and which peers to interact with. There is no global list to maintain, no administrator to petition for inclusion, and no single point that can fail or be corrupted.

The result is a network that behaves more like a living map than a registry — a constantly updating, verifiable reflection of who is speaking which business languages across the digital economy.

Through Directory Agents, the linguistic model of ecosystems gains its operational dimension.

Schemas and contract logic provide the semantics of trust; directories provide the topology of places where that semantics is in use.

Together, they enable a form of discoverable interoperability that is both humanly intuitive and digitally verifiable.

In this structure, ecosystems are not managed; they are spoken into visibility.

An agent that understands the language and makes itself discoverable becomes part of the conversation.

And that conversation — multiplied across countless agents, schemas, and contexts — is what ultimately forms the Internet Trust Layer itself.

6. What This Changes

Every new model of trust reshapes not only how systems interact but also how institutions think about authority. The linguistic model of ecosystems does both. It replaces the administrative machinery of inclusion with a semantic and verifiable fabric of understanding. The shift may appear subtle, but its effects reach deep into how digital collaboration, compliance, and innovation will evolve.

The first and most visible change is the disappearance of central registries.

In most trust frameworks today, registries serve as the anchor of confidence. They maintain lists of recognized issuers, certified verifiers, and approved participants. Their authority comes from control over who appears in the list. But in the Internet Trust Layer, no such lists are required. Authority emerges from verifiable definitions, not from enrollment.

When an agent’s schema and logic commitments can be independently verified, the registry’s function becomes redundant. Trust shifts from being a matter of inclusion to a matter of proof.

The second change is the democratization of participation.

Because ecosystems are defined by language, anyone capable of speaking that language correctly can participate. A small fintech can interact with a major bank if both follow the same schema and contract logic. A logistics provider in one jurisdiction can collaborate with a customs authority in another without prior integration. Participation becomes a matter of semantic alignment, not institutional status.

The third change is in governance itself.

In traditional ecosystems, governance bodies decide what is allowed. In ITL, governance becomes a property of the artifacts — of the schemas, the logic, and their versioning. Schema Management Agents and Contract Logic Management Agents don’t dictate behavior; they publish definitions that carry their own verifiable provenance. Agents can inspect, validate, and decide whether to adopt them. Governance, in this sense, becomes transparent authorship— it is the provenance of definitions rather than the enforcement of membership.

This redefinition of governance also transforms compliance.

Instead of relying on static certification, regulators and auditors can verify directly whether transactions conform to approved logic and schema definitions. Oversight becomes continuous and data-driven, not procedural. Compliance shifts from after-the-fact auditing to real-time verifiability.

The fourth and perhaps most profound change is interoperability by construction.

When ecosystems are defined by language rather than authority, compatibility is no longer negotiated between organizations — it is achieved automatically through shared semantics. The same way a web browser can render any page that conforms to the HTML standard, an ITL agent can interact with any other agent that uses compatible schema and contract logic. This makes interoperability a native property of the trust fabric, not an integration project.

Finally, this model transforms how innovation propagates.

In traditional systems, new capabilities spread through formal partnerships or standardization processes. In ITL, they spread linguistically: when a new schema or contract logic is published and gains adoption, an entire new ecosystem can emerge spontaneously. Innovators don’t need permission to introduce a new language; they only need others to find it useful.

Together, these shifts dismantle the slow and expensive scaffolding that has long limited digital collaboration. They make trust programmable, composable, and discoverable. They allow institutions to focus on the quality of their definitions rather than the policing of their memberships.

In this world, the credibility of an ecosystem depends not on who it admits, but on how clearly it speaks.

The more precise its vocabulary, the more rigorous its grammar, and the more verifiable its logic, the stronger its trust.

This is what changes when we move from membership lists to shared business languages.

Trust becomes measurable, participation becomes open, and governance becomes transparent. The digital economy stops acting like a series of gated communities and begins to function as a network of fluent participants — each contributing to a shared and verifiable conversation about value, risk, and responsibility.

7. Real-World Example

Abstractions become real when they meet the discipline of execution.

Consider a simple but universal case: a customer buys goods from a merchant, and both expect immediate payment and confirmation. Behind that expectation lies one of the most complex operations in commerce — synchronizing trust between parties who may never have interacted before.

In the traditional world, this trust is maintained by membership and intermediaries. Payment schemes, acquirers, and clearing houses ensure that only approved participants can exchange requests and confirmations. Every interaction happens inside a controlled network. That model works, but it scales poorly. It requires prior inclusion, constant oversight, and layers of reconciliation.

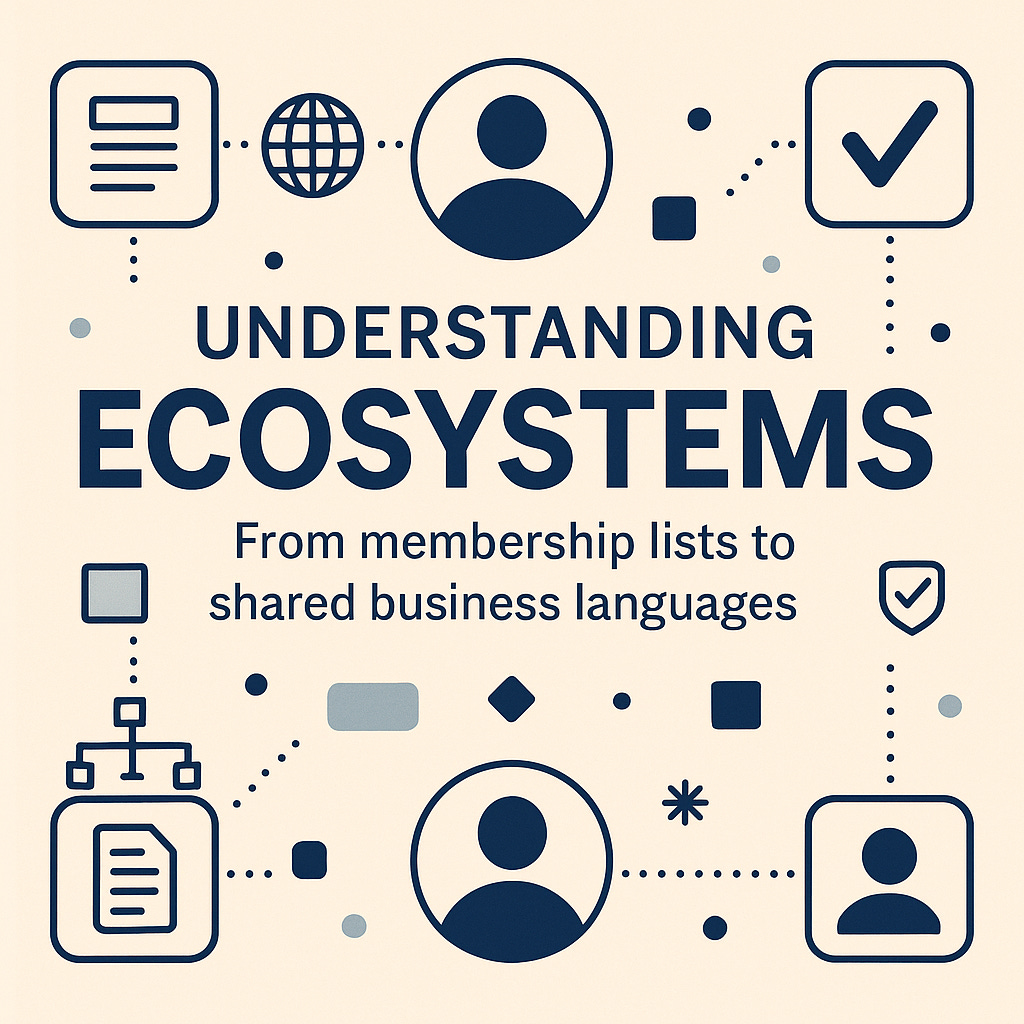

The Internet Trust Layer replaces this institutional choreography with verifiable interaction.

It introduces a new kind of participant: the Purchase Contract Agent, which acts as the coordinating context of the transaction. This agent doesn’t belong to any bank or platform; it represents the contract itself — the digital expression of agreement between buyer and seller.

The setup

Four agents participate:

A Customer Agent representing the buyer.

A Merchant Agent representing the seller.

A Bank Sub-contract Agent responsible for executing payment and settlement.

A Purchase Contract Agent (PCA) coordinating and finalizing the entire transaction.

Each operates autonomously. None are pre-registered in a common network, and no central authority supervises them. What connects them is their shared adherence to a Purchase Schema and a Settlement Logic — definitions published by two specialized management agents:

The Purchase Schema Management Agent defines the vocabulary — the data and credential structures for purchase orders, confirmations, and receipts.

The Settlement Logic Management Agent defines the grammar — the executable rules for verification, payment triggering, and contract finalization.

By establishing verifiable trust links to these definitions, each participant declares that it speaks the same business language. That commitment forms the ecosystem through which this purchase will occur.

The interaction

Initiation

The Customer Agent issues a Purchase Request Credential conforming to the shared Purchase Schema and sends it to the Merchant Agent.

The Merchant Agent verifies the credential’s structure and signature, confirms availability, and invites the Customer Agent to participate in a Purchase Contract coordinated by a specific Purchase Contract Agent (PCA).

Coordination

The PCA now assumes the role of orchestrator. It establishes a temporary contractual context — a verifiable coordination space in which all required participants (Customer, Merchant, Bank) are identified and authenticated.

Each agent commits its intent:

The Customer Agent signs a Payment Authorization Credential.

The Merchant Agent signs a Delivery Commitment Credential.

The Bank Contract Agent provides a Payment Reservation Proof.

Each credential is issued under the Purchase Schema and validated against the shared Settlement Logic.

Finalization

When the PCA has received all required inputs and verified their consistency, it executes the Commit Work phase — finalizing the contract.

It instructs the Bank Contract Agent to complete the payment, issues verifiable receipts to all participants, and records the finalized state in each participant’s micro-ledger.

The PCA then closes the context, and the contract ceases to exist as an active entity.

Post-transaction

The Customer and Merchant Agents hold verifiable proofs of the completed transaction.

The PCA may publish a minimal proof of completion to a Directory Agent for auditability or dispute resolution, without exposing sensitive data.

The ecosystem in motion

This simple purchase has now instantiated — and then dissolved — an entire ecosystem.

For a brief period, four independent agents operated under a shared language of trust. They aligned through schema and logic, coordinated through the Purchase Contract Agent, and completed the transaction without any central registry or membership list.

If another merchant or bank adopts the same Purchase Schema and Settlement Logic definitions, it becomes immediately discoverable to all participants who already use them. Ecosystem growth requires no onboarding — only shared meaning.

Should the Settlement Logic evolve, new versions can coexist with the old, allowing gradual migration. Each version represents a dialect; the ecosystem continues speaking, adapting naturally without centralized coordination.

The broader view

This example demonstrates how ITL transforms business transactions from procedural integrations into verifiable conversations.

The Purchase Contract Agent serves as the grammatical center — the digital equivalent of the “verb” in a sentence. It brings subjects and objects together, verifies intent, enforces logic, and issues outcomes.

Every completed contract becomes a proof of understanding between independent actors. Every proof strengthens the broader network of trust.

In this model, ecosystems are not infrastructures or institutions.

They are temporary alignments of meaning — born when agents agree on definitions, coordinated through verifiable logic, and concluded when their purpose is fulfilled.

That is what trust looks like when it becomes a property of language: no membership, no mediation, only shared understanding and verifiable execution.

8. Ecosystems That Speak to Each Other

In human society, no single language dominates every domain of life. We speak different languages at home, at work, and across cultures. Communication succeeds when there are translators, interpreters, or simply people fluent in more than one language. The same principle applies in the Internet Trust Layer: no single business language can serve every purpose, but agents that understand more than one can connect entire domains of activity.

In ITL, these multilingual agents are not special institutions; they are ordinary nodes that maintain verifiable trust links to multiple schema–logic pairs. Each link represents commitment to a specific business language. Together, these links define the agent’s linguistic repertoire — the set of ecosystems it can participate in.

The structure of interoperability

Consider again the payment ecosystem from the previous chapter.

A logistics company operating in ITL might also participate in a Shipping Ecosystem, defined by a shipping schema and contract logic for delivery confirmations. The company’s Person Agent already speaks this language. When it interacts with the merchant from the payment ecosystem, the two agents recognize overlapping contexts: one transaction concerns goods, the other money.

A multilingual Contract Agent can now act as a bridge between these two ecosystems.

It understands both the Payment Language and the Shipping Language. When the shipment is confirmed, it can automatically trigger a payment instruction using the logic of the other ecosystem. Because both schemas and logics are verifiable and their relationships explicitly defined, the Contract Agent doesn’t need external coordination. The result is seamless cross-ecosystem interaction — a shipping event causing a payment event through verifiable logic alone.

This is how ecosystems in ITL begin to speak to each other. They don’t merge or federate; they interact through shared meaning carried by multilingual participants.

Emergent value chains

Once multiple ecosystems interconnect this way, entire digital value chains can emerge spontaneously.

A financing ecosystem can integrate with a supply-chain ecosystem; an insurance ecosystem can interact with logistics and trade. Each retains its autonomy, governance, and semantics, yet interoperability occurs naturally wherever their definitions overlap or are linked through bridging agents.

This interoperability is not an afterthought; it is a structural property.

Because every schema and contract logic carries a unique, verifiable identity and explicit version history, references between them are unambiguous. A payment schema can cite a shipping schema as a prerequisite, or an insurance logic can depend on a risk-assessment logic published elsewhere. These semantic references act as translation points, enabling different ecosystems to align their meaning where needed.

The result is a network of networks — not in the old sense of federated infrastructure, but as a constellation of interoperable contexts. Each ecosystem defines its own rules of engagement, yet agents that share or bridge their languages can transact across them. The Internet Trust Layer becomes the grammatical framework that allows economic interaction to extend seamlessly from one domain to another.

Polyglot agents as economic interfaces

For institutions, this model has profound implications.

A bank’s Contract Agent may speak the languages of payments, settlements, and reporting.

A manufacturer’s Person Agent may speak the languages of procurement, logistics, and invoicing.

Where their languages intersect, new business interactions become possible without integration projects or bilateral agreements.

In effect, multilingual agents serve as economic interfaces. They don’t mediate trust; they make trust portable. By being fluent in multiple ecosystems, they enable information and value to move securely across boundaries that, in traditional systems, required costly coordination.

Ecosystem interoperability in practice

Imagine an international shipment where goods are financed, insured, and tracked through separate ecosystems. The shipping ecosystem records location and delivery events. The insurance ecosystem evaluates risk and coverage. The financing ecosystem releases funds upon verified delivery.

Each ecosystem operates independently, yet their agents interconnect through shared schema references and contract logic conditions. The moment a delivery credential is issued in the shipping ecosystem, it becomes a valid proof in the financing and insurance ecosystems. The ecosystems communicate not through governance agreements but through verifiable meaning.

This is the real power of the linguistic model: it scales horizontally through understanding.

Interoperability doesn’t require a new platform, consortium, or standard body — it only requires that participants express their intentions in verifiable languages others can understand.

In such a world, ecosystems cease to be silos. They become dialects of the same digital economy — locally optimized, globally comprehensible. Each contributes to the larger grammar of trusted interaction that defines the Internet Trust Layer.

9. Redefining Governance

Every trust system, no matter how decentralized, must answer a fundamental question: Who defines the rules?

In the traditional view of digital ecosystems, the answer has always been straightforward — governance bodies do. They publish frameworks, enforce standards, and approve participants. Governance, in that sense, means authority: the power to decide what is valid and who belongs.

In the Internet Trust Layer, that model no longer applies. There’s no governance body.

When ecosystems are defined by verifiable schemas and contract logic rather than by membership lists, the nature of governance changes completely.

It shifts from being a function of control to a function of authorship.

From authority to authorship

In ITL, rules are not dictated by a governing institution; they are expressed as publicly verifiable definitions — schemas and logic published by identifiable agents. Each Schema Management Agent (SMA) and Contract Logic Management Agent (CLMA) signs and publishes its definitions under its own decentralized identifier. These definitions are open, inspectable, and versioned.

An agent that decides to use them does so voluntarily, establishing a verifiable trust link to the author. This act doesn’t transfer authority; it acknowledges authorship. The author defines the language; the participant chooses whether to speak it.

In this structure, governance becomes a market of definitions. Competing versions of schemas and logic can coexist. Participants gravitate toward those that best reflect their operational needs, regulatory obligations, or ethical standards. The best-governed definitions are not those enforced by decree, but those that earn adoption through clarity, rigor, and transparency.

This model turns governance from a hierarchy into an economy of trust. It rewards precision and verifiability rather than compliance with institutional processes.

Transparent provenance as governance

Traditional governance relies on policy documents and committees to establish legitimacy. ITL replaces that with transparent provenance. Every schema and contract logic definition carries an immutable record of who authored it, when it was published, and how it has evolved. Every agent that uses it leaves a verifiable trace of that choice in its trust links.

This creates a living audit trail of governance in action.

Anyone can trace which definitions an ecosystem relies on, who maintains them, and what versions are in use.

Instead of governance being performed behind closed doors, it becomes an observable property of the network.

This transparency also strengthens accountability.

If a definition proves flawed or outdated, the community can respond by publishing improved versions, and participants can migrate by updating their trust links. No central body needs to coordinate the change. Governance evolves organically through informed choice, guided by verifiable information.

Regulatory alignment without centralization

One of the recurring fears in decentralized systems is that the absence of central control means the absence of regulation. In reality, the opposite is true.

Because schemas and contract logic are explicit, versioned, and signed, regulatory requirements can be codified directly into the definitions themselves.

A regulator can publish its own logic module or schema extensions — for example, specifying anti-money-laundering checks or reporting obligations — and participants can adopt them by linking to that regulator’s definitions.

Compliance thus becomes a verifiable property of language, not an institutional certification.

Every transaction can be validated in real time against the logic defined by the relevant authorities, and the proofs of compliance can be preserved as part of the transaction’s verifiable record.

This model doesn’t weaken regulation; it modernizes it. It transforms oversight from external monitoring into integrated verification.

Ecosystem self-governance

Because participation in ITL ecosystems is voluntary and dynamic, self-governance emerges naturally.

Participants who share a business language share responsibility for maintaining its integrity. They can propose extensions, publish corrections, and collectively evolve the definitions that support their work.

Each new version is both a governance act and a technical artifact — a living expression of collective intent.

This is governance without bureaucracy: rules expressed as code, consent expressed as linkage, and accountability expressed as provenance.

The new social contract of trust

What ultimately replaces the old governance frameworks is a new social contract — one written not in policy documents, but in verifiable logic.

In ITL, governance is not something imposed on participants; it is something they participate in through their use of definitions. Every schema and logic pair represents a compact of mutual understanding between authors and users. Each trust link is a signature of consent.

This redefinition doesn’t eliminate governance — it makes it intrinsic.

The structure of the network itself enforces transparency, authorship, and verifiability.

In such a system, governance is no longer the authority to command; it is the responsibility to define clearly, publish openly, and stand behind one’s definitions.

That is what it means to govern in the Internet Trust Layer: to author meaning that others can trust, verify, and build upon.

10. Toward a New Understanding of Digital Trust

For decades, the architecture of digital trust has been built around inclusion.

We created federations to decide who could log in, registries to decide who could issue credentials, and governance frameworks to decide who could participate. Each of these mechanisms gave structure to trust — but they also confined it. They built walls to protect it rather than networks to extend it.

The Internet Trust Layer begins from the opposite premise: that trust does not need to be protected by authority if it can be proven through interaction.

When proof replaces permission, the foundation of trust shifts from who you are allowed to be to what you can verifiably demonstrate.

This is where the idea of ecosystems finds its true meaning. They are not federations, associations, or membership circles. They are living networks of shared meaning — domains where agents can understand and verify one another because they speak the same business language.

Each ecosystem is defined not by who it admits, but by the schemas and contract logic that describe how its participants communicate and transact. Each agent’s participation is not recorded in a registry, but expressed as a set of trust links that declare which definitions it follows and which rules it abides by. And each ecosystem exists not as an organization, but as a context — an environment of shared semantics and verifiable behavior.

When Directory Agents make these participants discoverable, ecosystems become visible without becoming centralized. When multilingual agents bridge them, they begin to interoperate without negotiation. And when governance becomes authorship, they evolve without bureaucracy.

The result is a system where trust and interoperability become two sides of the same coin.

Every verifiable definition contributes to the overall fabric of understanding. Every transaction adds a new expression to the language of digital collaboration. Over time, the Internet Trust Layer becomes less a technology stack and more a shared grammar of reliable interaction — one that anyone can learn, use, and extend.

This reframing carries profound implications for how institutions, regulators, and innovators operate.

Banks, for instance, no longer need to join or manage closed networks to participate in digital settlements; they need only to publish and adopt the schemas and logic that define their trust domains. Regulators no longer need to enforce trust from the outside; they can embed compliance directly into the verifiable languages of interaction. Innovators no longer need permission to create new ecosystems; they can simply define new vocabularies and grammars that others may choose to adopt.

In such a world, digital trust becomes less about belonging and more about understanding.

It is not granted once and maintained by committees; it is earned continuously through the clarity of communication and the precision of proof.

The Internet Trust Layer reveals what has always been true in human society: trust is not a membership privilege — it is a product of shared meaning.

We trust what we can understand, verify, and relate to.

When systems begin to operate on that same principle, digital trust will cease to be a technical problem and become what it was always meant to be: a natural outcome of understanding between intelligent agents.

That is where this journey leads — from membership lists to shared business languages, and from authority to meaning.