I. Introduction: The ‘Someone Else’s Problem’ We Can No Longer Ignore

In popular culture, a “Someone Else’s Problem” (SEP) is a peculiar form of willful ignorance. It describes a problem that is technically visible to everyone, yet remains mentally invisible, because everyone unconsciously assumes someone else will be responsible for it. After years of working in and observing the financial industry, I’ve come to believe it is being defined by its own, deeply embedded SEP.

At the heart of this problem is an assumption, an idea so foundational that we’ve forgotten it’s an assumption at all: that a financial transaction is, at its core, a simple, private, bilateral affair between two parties—a Bank and its Customer. This two-party model was the bedrock for everything. It’s the blueprint upon which we built our fortresses of trust, our entire regulatory framework, and our sprawling, complex concept of “settlement.” It was a simple and elegant model that worked for a very long time.

But that bedrock is now cracking. The blueprint is obsolete. The reason is simple, and it’s staring us all in the face: a “someone else” has entered the room. This new participant isn’t just another guest waiting their turn; they are a structural, non-negotiable, essential part of the transaction itself. They are no longer an external entity we can “settle up with” later; they are a direct, required participant in the deal’s core logic. And because our foundational blueprint has no room for this third chair, the entire industry has defaulted to treating them as a “Someone Else’s Problem” in the truest, most dysfunctional sense of the phrase.

Rather than acknowledging that our core architecture is wrong, we are trying to patch it. We bolt on new intermediaries, new APIs, and new data silos, desperately trying to force this new multi-party reality onto an old bilateral foundation. We are building a “brittle patchwork”of temporary fixes and complex workarounds, all while hoping the center will hold. This patchwork is the direct and measurable source of the friction, cost, and systemic risk that now defines modern finance. Those endless, multi-day reconciliation loops aren’t a “feature” of the system; they are the grinding, shrieking sound of its architectural failure. The T+2 settlement lag isn’t a law of physics. It is the contractually-mandated time buffer required for massive, centralized institutions to manually and legally reconcile their conflicting private ledgers. We’ve just given this systemic failure a polite, technical name: “reconciliation.” It’s time to call it what it is: an architectural crisis.

My argument in this article is that we must stop patching and start building. We must recognize that the “someone else” is not a temporary problem but a permanent fixture in a new, more complex financial landscape. We need to build a new protocol layer for finance—an “Assurance Layer”—designed from the ground up for this multi-party, verifiable, and “pre-conciled” reality.

II. The New Participants Who Have Entered the Room

This architectural crisis isn’t a theoretical, “future of finance” problem that we can relegate to innovation labs and white papers. It’s an immediate, practical, and structural breakdown that is happening right now. The “someone else” isn’t just knocking on the door; they are already in the room, and our systems are visibly failing to cope. These new participants aren’t just using our old financial rails; they are attempting to become part of the core logic of the transaction itself. And they are all exposing the same, single point of failure: our architecture was built for two, but the world now requires three or more.

Let’s look at three concrete examples.

1. The Central Bank (e.g., The Digital Euro)

For decades, the relationship between commercial banks and central banks was clear. A bank’s customer paid another bank’s customer. This was a bilateral exchange of commercial bank money—essentially, a transfer of IOUs between the banks. The central bank’s role was that of the “settler of accounts,” the trusted intermediary that would, at the end of the day, reconcile the net positions between these banks using central bank reserves. The central bank was never a direct participant in the customer’s purchase; it was the plumbing that settled the bank’s ledgers afterward.

The Digital Euro, and similar Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs), shatters this model. A CBDC isn’t just a new settlement asset for banks; it’s a new form of money (a direct central bank liability) that can exist in a citizen’s wallet. A customer, in the very near future, may wish to make a single purchase using both commercial bank money (from their deposit account) and Digital Euro (from their digital wallet). Suddenly, the simple bilateral (Bank-Customer) transaction becomes a three-party affair: the Bank, the Customer, and the Central Bank are all active participants in one event. How do you atomically settle this? The bank’s private ledger and the ECB’s sovereign ledger are two completely separate, independent systems. Our current “patchwork” approach would require a hideously complex and risky reconciliation: did the bank’s part of the payment go through? Did the ECB’s part go through? What if one fails and the other succeeds? This isn’t just a “new payment rail”; it’s a fundamental break in the two-party trust model, and it introduces a new form of settlement risk our architecture was never designed to handle.

2. The FinTech (e.g., The FIDA Mandate)

In the traditional model, a bank’s data about its customer was its private, proprietary asset. It was the “oil” that fueled its internal risk models and product development, locked securely within its fortress walls. The bank controlled the data, and therefore, it controlled the “truth” of that data. The Financial Data Access (FIDA) regulation, and similar open banking directives, fundamentally reframes this relationship. With customer consent, a bank’s data is transformed from a private asset into a shared resource, and a FinTech provider now has a legal right to be part of the “transaction” of using that data.

This regulation, while supporting a valid goal of innovation, accidentally mandates a deeply flawed architecture. It is built on a “right to access” or “data pull” model. This model legally compels banks to build and maintain a vast, complex web of APIs that grant third parties direct access to raw customer data. This forces banks into the “Dumb Pipe” dilemma: we are legally required to do the most expensive, high-liability work—securing the ledgers, bearing the compliance burden—while FinTechs build the high-margin relationships on top of our infrastructure. We are being mandated to become a low-margin utility. This “data pull” architecture is the very definition of a “patchwork” fix. It doesn’t create a new, shared trust model; it just pokes thousands of holes in the old one, creating a “1-to-N liability problem” where a single breach at one of the thousands of “data users” can cascade into a systemic crisis. This is the absurdity of the “data pull” model: to verify a single fact (like “Is the customer over 21?”), a FinTech is encouraged to pull and store the raw data (the customer’s entire birthdate and home address), creating a massive, unnecessary attack surface. Our bilateral architecture, designed to hoard data, is utterly incapable of handling this new, multi-party reality in a secure or strategic way.

3. The Financier (e.g., Embedded Finance)

Think about how a financed purchase used to work. A customer wanted to buy a sofa from a merchant. If they needed a loan, they would separately go to their bank, apply for financing, get the funds, and then return to the merchant to pay. This was a clean, two-step process involving two distinct, bilateral relationships: (Customer-Bank) and (Customer-Merchant).

“Embedded Finance” (or “Buy Now, Pay Later”) makes this process “seamless” by making the financier “invisible”—and in doing so, it creates a hidden risk. The customer clicks “buy,” and the financing is embedded directly into the checkout button. The lender (the “financier”) is now an invisible third party to the purchase. The simple (Customer-Merchant) sale has become a complex, three-party (Customer-Merchant-Financier) event. This creates a “catch-22” of settlement risk: the purchase cannot happen unless the financing is approved, but the financing will not be released unless the purchase is confirmed. Our current systems “solve” this with—you guessed it—more risky and complex reconciliation. The financier pays the merchant, hoping the sofa is shipped. The merchant ships the sofa, hoping the financier’s payment clears. This settlement risk is the direct and unavoidable result of trying to simulate a three-party agreement using two separate bilateral “patches.”

These three examples—the Central Bank, the FinTech, and the Financier—are not isolated cases. There are more, in both retail and wholesale banking. They are the same pattern repeating, the same “someone else” appearing in different costumes. They are all symptoms of the same underlying architectural failure. Our systems were built for two, but the world now demands three or more.

III. Why Our Current “Solutions” Make the Problem Worse

The architectural crisis I described in the last chapter—this sudden, forced introduction of a “someone else” into our bilateral systems—is not a secret. The industry is acutely aware of the friction. The problem is that our responses to this crisis, the “solutions” currently on the table, are not solutions at all. They are merely two different, and equally dysfunctional, ways of deepening the problem. They fall into two distinct camps: either we double-down on the old, broken model, or we chase a new, seductive model that completely misunderstands the nature of finance.

Failure 1: The “Patchwork of Intermediaries” (The Old Way)

The first response is the path of least resistance. It’s the default behavior of any large, established system: when faced with a new reality, try to patch it onto the old one. This is the “fortress” mentality of 20th-century banking. Our institutions are silos—secure, opaque, and self-contained. When a new participant (like the FIDA-mandated FinTech) appears, the legacy response is not to re-imagine the architecture, but to build another silo and connect it with a brittle “patch,” typically a complex API. We are trying to solve a network problem by reinforcing our silos.

The FIDA regulation, in its current interpretation, is a perfect case study of this failure. The “data pull” model it mandates—forcing banks to build and maintain a “vast, complex web of APIs” to grant third parties direct access to raw customer data—is the very definition of a patch. It doesn’t create a new, shared trust fabric; it just pokes thousands of new holes in the fortress walls. This forces banks into the “Dumb Pipe” dilemma: we are legally mandated to become a “low-margin, high-risk utility,” doing all the expensive, high-liability work of securing the ledgers while FinTechs build the high-margin relationships on top.

This API-driven “patchwork” doesn’t solve the problem of reconciliation; it multiplies it. It creates a “1-to-N liability problem” where a single data breach at one of the thousands of “data users” can cascade into a bigger crisis. This entire model is an “API Hell,” a tangled, expensive web of legal agreements and brittle connections that attempts to simulate trust rather than create it. This is the core of the failure: the “innovation gap.” The patchwork approach doesn’t close this gap; it just creates thousands more of them.

Failure 2: The “Category Error” of Tokenization (The New Way)

The second response is the “revolutionary” one: tokenization. This approach, built on blockchain and public ledgers, is seductive because it correctly identifies the problem (centralized intermediaries) but prescribes a solution that is based on a profound misunderstanding of the domain. Tokenization commits a fundamental “category error”: it attempts to manage institutional facts (like money, ownership, and contracts) as if they were digital objects (brute facts).

Let me explain. A brute fact is a simple, physical reality. A rock is a brute fact. A digital token, as a unique string of bits, is also a brute fact. Its existence is self-evident. A institutional fact, by contrast, is a social and legal agreement. It has no physical reality; it exists only because we have collectively agreed to give it a function. “Money” is an institutional fact. “Ownership” is an institutional fact. “Marriage” is an institutional fact. Finance is not a system of objects; it is, and has always been, a system of promises, obligations, and stateful relationships—all of which are institutional facts.

Tokenization fails because it tries to represent a complex, stateful, multi-party relationship as a simple, transferable object. A token is a pathetically inadequate data structure for this job. Consider the “tokenized house”. The token model asserts that “possession of the private key” (a brute fact) is the same as “legal ownership of the house” (an institutional fact). But what happens if a court orders the asset frozen, or a thief steals the key? The blockchain (brute fact) and the legal system (institutional fact) are now in violent disagreement. The token has failed to represent the real-world truth.

Now apply this to the multi-party problems from Chapter II. How do you represent a complex, three-party Embedded Finance deal (Customer-Merchant-Financier) with a single token, or even with multiple tokens? How do you represent a revocable FIDA consent agreement with a transferable token? You can’t. The token is the wrong tool for the job. It’s a two-party asset barter model being misapplied to a multi-party contractual relationship problem.

Both of these “solutions” are dead ends. The old way—the “patchwork”—is architecturally unsound, multiplying the very reconciliation problem it claims to solve. The new way—”tokenization”—is both philosophically and technically unsound, mistaking the very nature of finance. We don’t need to patch our broken silos, and we don’t need a new system for tracking digital objects. We need a new foundation, a third path that is designed to do the one thing neither of these models can: verifiably manage multi-party agreements.

IV. A New Foundation: From Managing Objects to Verifying Agreements

If the “patchwork” of intermediaries is an architectural dead end, and “tokenization” is a philosophical one, we are left in a state of profound crisis. We are stuck between a past that no longer works and a future that cannot work. We have correctly identified the “someone else” in the room, but we have no coherent and natural way to interact with them. To find a third path, we must stop looking at our current systems and ask a much more fundamental question: What is it, exactly, that we are trying to build?

The solution cannot be another asset (like a token) or another silo (like a new clearinghouse). The solution must be a new, missing protocol layer for the internet itself—an “Assurance Layer” that is designed to do the one thing the internet’s original protocols could not: manage verifiable agreements. The internet was built to move data (brute facts) with no opinion on its truthfulness. We must now build the layer that can create and verify agreements (institutional facts).

To do this, we first have to be honest about what finance is. As we explored in the “category error” of tokenization, finance is not a system of objects; it is a system of promises, obligations, and stateful relationships. These are “institutional facts,” not “brute facts.” An institutional fact is a form of social reality: it doesn’t exist as a physical object, but only because we have collectively agreed to give it a function. “Money” is an institutional fact. “Ownership” is an institutional fact.

The powerful, recursive logic that all human institutions use to create these facts has been defined by the philosopher John Searle as the “Social Reality Engine”: X counts as Y in C. This is the simple, foundational “grammar” of our entire social and economic reality.

A piece of paper with green ink (X) counts as “Twenty Dollars” (Y) in the context of “the U.S. monetary system” (C).

A person raising their hand (X) counts as “a ‘Yes’ vote” (Y) in the context of “a formal board meeting” (C).

Our financial architecture is failing because it misunderstands this grammar. Tokenization tries to make X (the token) be Y (the value), while completely collapsing the C (the context). The “patchwork” model tries to connect multiple, incompatible C‘s (the silos) with brittle, insecure patches.

A true solution, a real “Assurance Layer,” must be built to execute this formula directly. This is the architecture of the Internet Trust Layer (ITL), and it is built on these three, precise primitives:

1. X is the Evidence (The Verifiable Credential)

The X term is the brute fact input, the evidence. In the ITL, this is not a transferable object like a token. It is a statement of fact from an accountable source—a Verifiable Credential (VC). It is held by an identifiable and accountable identity. This distinction is everything. A token is anonymous and its value is based on possession; a VC is signed by a known issuer and its value is based on provenance. It is “admissible evidence.” A VC from a bank attesting that “€10,000 is earmarked” is not the money itself; it is a cryptographic promise from the bank, a verifiable brute fact that can be presented as evidence in a formal agreement. Unlike a token, a VC can also represent complex, real-world facts: a non-transferable fact (like a university degree), a revocable fact (like a driver’s license), or a stateful fact (like a KYC approval).

2. Y is the Logic (The Deterministic Finite State Machine)

The Y term is the status function—the set of rules that creates the institutional fact. This is the “engine” of the institution. In the ITL, this logic is a Deterministic Finite State Machine (FSM)—a piece of code that defines the rules of the agreement. For example, the FSM defines the logic: “The presentation of a valid VC from the Bank (X1) and a valid VC from the ECB (X2) counts as ‘Settlement Complete’ (Y).” This FSM provides Process Integrity—cryptographic proof that the act was valid according to the rules—which is infinitely more valuable than the “Data Integrity” of a blockchain (which just proves a record is unchanged, not that it was valid in the first place).

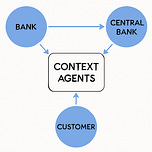

3. C is the Context (The Context Agent)

This is the most critical and revolutionary component. The logic (Y) is only valid within a specific, bounded Context (C). “A raised hand” only counts as a “vote” in the meeting. Outside that context, it’s just a stretch. Our current financial system is failing because its contexts are wrong. The “patchwork” model has rigid, siloed contexts (the banks). The “tokenization” model has one giant, public context (the global ledger), which leads to “context collapse”: a catastrophic failure of privacy, governance, and security.

The ITL’s master innovation is that it allows participants to create a Context Agent—a private, disposable, single-purpose “vessel” for one single deal. When you, your bank, and the ECB need to settle a multi-party payment, you don’t transact on your separate systems or on a public blockchain. Instead, you all join a new, temporary, and private Context Agent that contains the one FSM (the “rulebook”) you all agree to for that one event. This is the “digital room” where the deal happens. This architecture is private by default, infinitely scalable, and perfectly aligned with the legal reality of contracts, which are bounded agreements between known parties.

V. The Solution: The “Someone Else” Becomes a Co-Participant

The architecture we defined in the last chapter—the “Social Reality Engine” of X, Y, and C—is not just a theoretical framework. It is a practical, engineering-level blueprint for a new financial system. Its power lies in how it completely inverts the dominant, broken model of “transact, then reconcile.” This inversion is the key to solving the “Someone Else’s Problem” for good.

Our current system, the “patchwork of intermediaries,” is built on a sequence of blind hope. Parties transact in their separate, opaque silos and then spend days in a slow, expensive, and risk-laden process of “reconciliation” to see if everyone else also did what we assumed they do. The ITL model, by contrast, is one of “pre-conciliation.” It moves the agreement, the verification, and the binding of all parties to the front of the process. The execution of the deal is the final, atomic, instantaneous result of this “pre-conciled” agreement.

Let’s see what this looks like in practice.

The Old Way (The Problem): Two Separate Events, One Reconciliation Gap

In the legacy model, when our “someone else” (be it the ECB, a FinTech, or a Financier) enters the deal, the architecture forces us to simulate a three-party agreement by executing two (or more) separate, bilateral transactions.

Event 1: The Bank and its Customer interact in their private silo. A payment instruction is sent.

Event 2: The Customer (or the Bank) separately interacts with the “Someone Else” (e.g., the ECB) in their private silo.

The Reconciliation Gap: A dangerous, uncertain space now exists between these two events. Did Event 1 succeed but Event 2 fail? What if the FinTech’s FIDA data pull (Event 2) happens before the bank’s internal fraud check (Event 1) is complete? What if the Embedded Financier’s funds (Event 2) are released, but the merchant’s sale (Event 1) fails? This gap is where all settlement risk lives. The entire multi-trillion dollar clearing and settlement industry exists just to manually and legally bridge this architectural flaw.

The ITL Way (The Solution): One Single, Atomic Event

The Internet Trust Layer’s architecture makes this reconciliation gap a logical impossibility. It doesn’t bridge the silos; it replaces them with a single, temporary, and private “digital room” for the deal.

Here is the workflow. Let’s use the Digital Euro example from Chapter II, where a Customer wants to pay a Merchant using both commercial bank money and ECB-issued Digital Euro.

Instantiation: Instead of transacting on separate ledgers, all four parties—the Customer, the Merchant, the Commercial Bank, and the ECB—are invited to join a new, private, single-purpose Context Agent (C). This agent is created just for this one deal and is then dissolved.

Agreement on Logic: This Context Agent contains the single, agreed-upon “rulebook” for this event: the Deterministic Finite State Machine (Y). This FSM’s logic is transparent and binding on all four parties. It might state: “This transaction counts as ‘Settled’ if and only if a valid VC from the Bank for €50 and a valid VC from the ECB for €50 are both presented to the Context agent.”

Presentation of Evidence: Each participant submits their cryptographic promise, their Verifiable Credential (X), to the Context Agent.

The Customer’s agent presents a signed “Payment Authorization.”

The Bank’s Integration Agent attests: “I, the Bank, have earmarked €50 (X1).”

The ECB’s Integration Agent attests: “I, the ECB, have earmarked €50 (X2).”

Atomic Execution: The Context Agent—acting as a neutral, automated, and digital referee—receives these VCs. It has no loyalty to any single party. Its only job is to execute the FSM. It sees that X1 is valid, X2 is valid, and the Customer’s authorization is valid. The conditions of the FSM (Y) are now met.

The Settlement: The FSM fires. In a single, logical, atomic instant, the institutional fact of “Settlement” is created. The ownership of the Bank’s €50 and the ECB’s €50 is transferred to the Merchant according to the legally binding commitments from the Bank and the ECB. There is no reconciliation gap. There is no moment in time where one part has settled and the other has not. The transaction is the settlement.

This same pattern solves our other examples. For FIDA, the Bank, Customer, and FinTech join a Context Agent whose FSM logic is the “Financial Data Sharing Scheme.” The FSM requests the fact (e.g., “proof of income > €50k”) from the Bank’s agent, and only upon receiving it does it execute the rest of the FinTech’s logic. The “1-to-N liability problem” vanishes, replaced by a self-contained, auditable digital contract. For Embedded Finance, the Customer, Merchant, and Financier join a Context Agent whose FSM is the checkout. The FSM receives the legally binding signed “Financing Earmarked” VC (X1) and the “Merchant Goods Earmarked” VC (X2) and atomically swaps them. The risk is gone.

This is the solution. The “someone else” is no longer a “problem” to be patched or an external silo to be reconciled with. They are simply another co-participant, an equal and verifiable member of a single, unified, and “pre-conciled” institutional act.

VI. The Payoff: What Happens When the “Problem” Disappears?

The “pre-conciliation” model we explored in the last chapter—where all participants join a single, private “digital room” to execute a unified, atomic event—is more than just a technical solution. It is a phase change. It is a fundamental re-architecting of how trust and value operate, and its consequences are profound. When the “reconciliation gap”—that dangerous, friction-filled void at the heart of our current system—is finally designed out of existence, we are left to contemplate what the financial world looks like without it.

This is a profound re-alignment. The most immediate and obvious payoff is that the transaction becomes its own reconciliation. When the Context Agent’s (C) deterministic logic (Y) fires, its final act is to create and issue a Verifiable Credential-Receipt. This is not a simple “payment confirmed” message. It is the durable, portable, and indisputable cryptographic proof of the finalization of the entire, multi-party institutional act. This single, signed VC-Receipt is delivered to all participants in the deal.

This one act creates what I call a “digital double-entry bookkeeping” model for the entire economy. Each participant’s private, sovereign Micro-Ledger (their institutional memory) receives the identical, shared, and mathematically verifiable proof of the event. Your books and my books are now, by definition, “pre-conciled.” The entire, multi-trillion dollar industry of back-office reconciliation—an industry that exists only to bridge the architectural flaw of our siloed systems—is rendered obsolete. The transaction is its own audit trail that can be taken to courts in case of any dispute.

The second, and perhaps more powerful, payoff is the elimination of settlement risk. That “asynchronous risk-state” that plagues all of finance—the “payment sent, asset not received” catch-22 from our Embedded Finance example—becomes a logical impossibility. Within the Context Agent, the transfer of the Bank’s promise (X1) and the ECB’s promise (X2) is not two events, but one. This enables true, atomic Delivery-versus-Payment (DvP) or Payment-versus-Payment (PvP) for the first time. The economic consequences of this are staggering. Why does our system run on a T+2 or T+1 settlement delay? To create a time buffer for our slow, manual reconciliation process. And what does that time buffer legally require? It forces the entire industry to park thousands of billions of dollars in “non-productive, risk-mitigating” capital as collateral against the risk that someone in the chain will fail. When settlement is instant and atomic, this trapped capital is liberated, fundamentally altering capital efficiency for the entire global economy.

Finally, let’s look at the strategic payoff, particularly for the FIDA problem. The “data pull” (API) model forces banks into the “Dumb Pipe” dilemma, a high-risk, low-margin compliance cost. The ITL’s “evidence push” model, by contrast, creates an entirely new, monetizable business model. The bank’s payoff is that it escapes the “plumber” role and becomes a “chef”. Its new product is not raw, high-liability data, but “billable facts.” A FinTech will pay for a bank-signed, cryptographically-secure Verifiable Credential that says “Fact: KYC-Verified” or “Fact: Income > €50k.” This “bankable instrument” is far more valuable and infinitely less risky than the raw data dump it would get from an API. The bank transforms a compliance cost into a new revenue stream.

This is the payoff. The “Someone Else’s Problem” is not just “solved”; it’s transformed into an opportunity. We move from a high-friction, high-risk, privacy-collapsing system of “global truth” (public ledgers) or “siloed truth” (isolated transactions on private ledgers) to a private-by-default, scalable, and capital-efficient model of “verifiable, shared truth”.

VII. Conclusion: Stop Patching, Start Building

The “Someone Else’s Problem” that we’ve explored—this new, essential participant who breaks our bilateral financial model—is not a localized issue. It is not a temporary bug. It is a symptom of a much larger, historical reckoning. The Digital Euro, the FIDA mandate, and the rise of Embedded Finance are not isolated challenges; they are the first tremors of a big shift, revealing the profound inadequacy of the foundation upon which our entire digital economy was built.

We are living through the consequences of the internet’s “original sin.” The first great leap of our age, the Internet, solved the problem of Connection. It was a brilliant “brute-data” network designed to move data with perfect fidelity, but it was built with no native protocol for managing agreement. It had no opinion on the truthfulness or provenance of the data it carried. This left us in a “polluted ocean of unverified, brute data”.

The second great leap, Artificial Intelligence, is now solving the problem of Comprehension. It gives us brilliant synthesizers that can interpret and generate answers from that polluted ocean with perfect, human-like confidence. But in doing so, it only deepens the crisis of trust, as it has no way of distinguishing fact from “hallucination”.

We are now faced with the third, and final, leap: the challenge of Assurance. We have connected everything and we can comprehend anything, but we can verify almost nothing. Our entire, sprawling, high-speed digital economy is built on a “brittle trust” model, a patchwork of slow, expensive, and fallible centralized intermediaries (like banks, credit bureaus, and clearinghouses) trying to manually stand in for the internet’s missing trust protocol.

This is the context for our failure. The two “solutions” we’ve clung to, of which one does not work any more and the other cannot work going forward, are merely failed attempts at this Third Leap. The “patchwork of intermediaries” is the old world’s attempt, trying to build trust by reinforcing its 20th-century silos. “Tokenization” is the new world’s attempt, trying to build trust by mistaking an institutional promise for a digital object. Both are dead ends.

The architecture I have laid out in this article—the Internet Trust Layer, built on the “Social Reality Engine” of X counts as Y in C—is the blueprint for this Third Leap. It is the missing “Assurance Layer” designed to finally manage and verify agreements as a native function of the digital world.

It provides a “bedrock of truth” by giving us the tools to manage “institutional facts.” The Verifiable Credential (X) gives us a way to make verifiable promises. The Deterministic Finite State Machine (Y) gives us a way to create verifiable logic. And the private, disposable Context Agent (C) gives us a way to manage verifiable, multi-party contexts.

This is the path forward. The multi-party future of finance is already here. We can no longer afford to treat it as “Someone Else’s Problem,” a glitch to be patched onto our obsolete bilateral systems. We must stop building on a broken foundation of brute-fact objects and start building on a sound foundation of verifiable, institutional-fact agreements. The reconciliation — and innovation — gap is not a feature to be managed; it is a flaw to be eliminated.

We must stop patching. It’s time to start building.