1. The Illusion of Stability

Stablecoins have been branded as the safe haven of digital finance—the dependable bridge between traditional money and the volatile world of crypto assets. Pegged 1:1 to fiat currencies and often backed by high-quality reserves, they present themselves as neutral instruments: stable in price, liquid in form, and indifferent to the chaos they surround.

But what if this stability is a mirage?

Imagine a digital token, perfectly collateralized with U.S. Treasury bills, offering instant redemption and regular attestations by a top-tier auditor. It looks like the safest asset in the crypto ecosystem. Now imagine that same token is used as the unit of account, store of value, and medium of exchange across a trillion-dollar speculative landscape—NFTs, meme coins, yield-farming schemes, and exotic derivatives spun from abstractions. Suddenly, the market realizes that the entire digital edifice built atop this token has no enduring economic value. Panic sets in.

Redemptions flood in. The issuer begins liquidating its reserves—those same high-grade Treasury bills—to meet outflows. Prices wobble. Yields spike. Funding markets ripple. What was once an island of stability becomes the first domino in a much larger chain reaction. Not because the stablecoin failed in its technical design—but because it succeeded in its adoption into an ecosystem that was economically empty.

This is the paradox at the heart of the stablecoin promise: it is not enough to peg a coin to something stable. The real question is what the coin enables—and what happens when that purpose evaporates.

Stablecoins don’t exist in a vacuum. Their use matters more than their backing. When they circulate primarily to fund speculative behavior, they inherit the fragility of that behavior. When they serve as the gateway to synthetic leverage and uncollateralized risk, their apparent stability masks a systemic vulnerability.

In this sense, stablecoins are the most dangerous kind of asset: one that looks safe, behaves like money, and yet contributes nothing to the production of trust.

This article will explore what happens when we flip the stablecoin over—when we examine its mechanics, incentives, and systemic role, not just its peg. We’ll see how even the best-designed stablecoin, when misused, can destabilize not just crypto markets, but traditional ones too. And we’ll explore a fundamentally different approach to digital money—one built not on tokens, but on verifiable contracts between real economic agents.

Because true stability in money doesn’t come from backing alone. It comes from context, accountability, and a binding relationship between value and trust.

2. The Design Flaw Hidden in Plain Sight

At first glance, the architecture of a modern stablecoin seems unimpeachable. A user deposits one dollar, receives one digital token. The issuer invests the dollar in short-term government securities—T-bills, reverse repos, or overnight deposits—and holds them in custody with a regulated bank or fund administrator. The token can be redeemed at any time, one-for-one. Independent auditors confirm the reserves. What could possibly go wrong?

But that apparent soundness conceals a structural flaw—one not of engineering, but of economic misalignment.

To begin with, the stablecoin issuer earns the yield. Not the user.

The user hands over an interest-bearing fiat instrument—money that could be deployed in the real economy or held in a bank account earning yield. In return, they receive a zero-yield digital token, created for convenience, speed, or interoperability. Meanwhile, the issuer invests the reserves in short-term debt and pockets the interest. When interest rates are high, that interest becomes massive. At today’s yields, a $1 trillion stablecoin would generate tens of billions in annual income—without lending a cent to the productive economy.

This is not a flaw of bad management or insufficient disclosure. It is a feature of the model itself. Stablecoin issuers monetize the yield spread between user deposits and public debt markets, but bear no economic risk, create no credit, and perform no intermediation in the traditional sense. They are not lenders. They are liquidity pass-throughs with embedded toll booths.

The result is a reverse distribution of monetary value: users give up yield for access to a tokenized casino; issuers reap the profits while offering no upside, no dividends, no participation in governance or risk. In traditional banking, this would be a scandal. In stablecoin economics, it is just another product feature.

But the design flaw runs deeper still. Stablecoins are treated as neutral carriers of liquidity, but in reality, they are economic enablers. They do not merely sit on the sidelines—they underwrite the speculative core of the crypto economy. They provide the unit of account and base liquidity for decentralized lending, token swaps, yield schemes, synthetic asset issuance, and perpetual contracts. Without stablecoins, most of the infrastructure of decentralized finance (DeFi) collapses instantly.

So while the reserves may be risk-free, the demand they serve is not. And when that demand vanishes—because the assets it supported are revealed to be worthless, circular, or fraudulent—the stablecoin must still fulfill its obligations. This is where the liquidity inversion begins. The stablecoin must suddenly redeem at scale into fiat, which means selling the very government securities that gave it credibility in the first place. The instrument flips: from a passive stabilizer to an active disruptor.

And this is the essential flaw: stablecoins are not designed to fail gracefully. They either function or flood. There is no elasticity. No protocol-layer throttling. No awareness of the context in which they are used.

Unlike regulated banks, they are not integrated into lender-of-last-resort mechanisms. Unlike mutual funds, they have no embedded liquidity gates. Unlike legal contracts, they do not express who owes whom, under what terms, or why.

In short, they are money without meaning—and meaning is what makes money trustworthy.

3. Systemic Risk on Redemption Day

Stablecoins promise instant convertibility—but convertibility, under stress, becomes their most dangerous feature.

Imagine a scenario where a widely used stablecoin—let’s say SolidUSD—has grown to a market capitalization of $1 trillion. It’s fully backed by short-term U.S. Treasury bills and reverse repos, with real-time audits and strong redemption assurances. Institutions, traders, and DeFi protocols treat it as the de facto digital dollar. Its presence is everywhere—from liquidity pools and derivatives to payroll services and remittances.

Then, the collapse begins.

Not in the stablecoin itself, but in the economy it underwrites. The speculative tokens, NFT collections, synthetic assets, and self-referential lending structures that formed the bulk of on-chain activity are revealed, almost overnight, to be fundamentally worthless. A series of defaults, price crashes, and margin spirals wipe out hundreds of billions in “value” across the digital asset ecosystem.

What follows is not a crisis of confidence in the stablecoin’s reserves—but a crisis of confidence in why anyone would want it anymore.

The redemption floodgates open—not because users distrust the stablecoin, but because they no longer need it. The economic activity it lubricated has collapsed. Now, users just want their fiat back.

The issuer, per its design, honors redemptions. But that means selling its reserve assets—hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of short-term Treasuries—into an already stressed market. And here’s where the systemic risk takes shape:

Treasury yields spike. Prices drop as redemptions force mass selling.

Funding markets ripple. Repo markets, money market funds, and institutional cash managers are hit by collateral markdowns and rising funding costs.

Liquidity evaporates. Investors who thought they were holding “safe” assets find they are illiquid at the moment they need them most.

Cross-market stress multiplies. Banks, brokers, and asset managers—already operating in a fragile post-tightening environment—face margin stress, withdrawals, and exposure to instruments they assumed were cash equivalents.

What began as a redemption from a sound, fully backed stablecoin turns into a broad-based liquidity crunch across the financial system.

And here lies the core insight: even a perfectly collateralized stablecoin becomes dangerous when used at scale to fund an economy that isn’t real. Because money—when it floods back from fiction to fiat—must be converted somewhere. And that “somewhere” is the real-world financial system: public debt markets, institutional funding pipelines, and bank liquidity buffers.

This dynamic is uniquely destabilizing. It’s not a bank run. It’s a reverse monetary tsunami: synthetic demand that once inflated digital markets violently unwinds, forcing the liquidation of real assets to redeem fictional ones. The stablecoin didn’t fail. But the fiction it financed did—and the effects are transmitted not through insolvency, but through redemption pressure, magnified by scale.

And unlike in traditional financial networks, there is no protective architecture. No capital buffers, no central bank lines, no systemic risk supervision. The issuer was compliant. The reserves were sound. But the design was blind to how and why the instrument was used.

What’s revealed is that stablecoins may not need to fail in order to cause a financial crisis. They just need to be successful in the wrong economy.

4. Stablecoins Are Money Without a Contract

Traditional money is never just a bearer instrument. It is a contract in context—a promissory note, a deposit liability, a claim against a known party under a specific legal and regulatory framework. Every form of money we trust—whether it’s central bank cash, commercial bank deposits, or short-term government securities—is rooted in a system of enforceable relationships. Those relationships give money its most important feature: meaning.

Stablecoins abandon this principle.

While marketed as “digital dollars,” stablecoins lack the defining structure of monetary instruments: they are not bound to identifiable parties, not linked to verifiable obligations, and not born in the act of economic exchange. They circulate freely between anonymous wallets, wrapped in technical assurances but stripped of legal, relational, and contractual context.

This might appear elegant—“neutral,” even—but it comes at a profound cost.

Without context, a stablecoin is unattached liquidity. It does not express why it was issued, who issued it on behalf of whom, or what the underlying economic purpose is. It is money that simply exists, detached from the accountability chain that defines legitimate financial instruments.

In a functioning economy, money creation reflects intentional acts—a loan agreement, a securities issuance, a payment against an invoice. Each is a contract, verifiable by law and enforceable by institutions. But a stablecoin is not issued in the act of an agreement; it is issued in exchange for fiat—a blank abstraction, not a bounded commitment.

And this is where its systemic danger hides.

Because it appears frictionless and freely transferable, the stablecoin becomes the preferred settlement token for everything unregulated. It is the payment rail for speculation, for synthetic leverage, for gamified finance. But no matter how advanced its code or how secure its custody, the stablecoin has no way to distinguish between a legitimate transaction and a fabricated one, between value creation and value illusion.

It is a financial instrument without discrimination, and therefore without responsibility.

When things go wrong, the stablecoin does not unwind through contracts. It does not terminate through structured legal processes. It simply flows outward in a panic, converting synthetic claims into real-world liquidity demands. And because no one knows who owes what to whom, the impact is absorbed indiscriminately—by markets, not relationships.

Contrast this with money issued via contracts—through a bank loan, a payment claim, or a trusted agent in a verifiable network. There, money only exists because parties have made binding, reciprocal commitments. When such systems fail, they fail within a framework—losses are knowable, claims can be reconciled, liability is traceable.

This is the kind of architecture the Internet Trust Layer envisions: a digital economy where every transaction is an agreement between agents, where money is the outcome of contract execution, not a precondition. In such a model, monetary claims are verifiable, scoped, and finite—because they were created to reflect something real.

Stablecoins represent the opposite. They are boundless liquidity with no ledger of intent, no audit trail of obligation, and no structural path to resolution when the economy they fuel collapses.

In short, they are money without a contract. And that makes them trustless in the most dangerous sense of the word.

5. The Flipped Coin: What the Other Side Looks Like

If the face of the stablecoin is smooth, shiny, and seductively simple, the reverse reveals the complexity it hides: unearned yield, systemic fragility, and economic detachment. But what does the other side of the coin—the truly stable one—actually look like?

To answer that, we need to invert the assumptions that stablecoins rest upon. Instead of money that floats free, imagine money that is anchored to context. Instead of tokens issued in advance, imagine monetary claims that are born from transactions. Instead of speculative velocity, imagine trustable finality—where every monetary action has a known purpose, counterpart, and contractual boundary.

This is not hypothetical. It is the architecture envisioned by verifiable agent-based transaction networks—like the Internet Trust Layer (ITL). In these systems, the unit of value isn’t a token; it’s a verifiable claim, issued as the outcome of a contract executed between identifiable parties. These contracts are not smart in the blockchain sense—they are smart in the legal, economic, and trust sense.

Here’s how that looks in practice:

A buyer and seller negotiate terms for a transaction. A contract agent mediates the agreement and verifies all required conditions—identity, capacity, obligation.

Once preconditions are met (e.g., payment committed, service rendered), the contract agent issues a credential—a signed, cryptographically verifiable claim that settlement has occurred.

If payment is required, it is not pulled from a pool of tokens, but created as a CoBDC—a commercial bank digital currency issued as a contract output, under the full backing of the bank and under regulatory oversight.

The CoBDC is not transferrable to an anonymous wallet. It is context-bound, only valid for the intended parties and only for the duration of the contractual context.

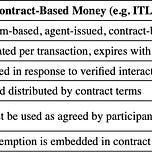

This model flips the coin in every meaningful way:

This design eliminates the possibility of synthetic liquidity sloshing through opaque systems, because there is no free-floating liquidity to begin with. Every issuance is tied to an identity, a contract, a responsibility, and a termination condition.

It also removes the perverse incentives. No one earns risk-free yield by printing tokens. No one gives up their interest just to get access to speculation. Every actor’s gain is bound to their contribution to a real transaction.

Most importantly, this model introduces failure modes that are graceful. If a contract fails, its money fails with it—locally, privately, verifiably. There is no system-wide run, no mass liquidation of T-bills, no collapse of trust in the monetary instrument itself.

This is the true “other side” of the coin: a monetary system where money is no longer a floating claim but a closing statement. A record of something real. Something done. Something trusted.

That’s what stability actually looks like.

6. Regulation Will Come — But It May Miss the Point

The systemic risks posed by stablecoins are no longer hypothetical. Policymakers, central banks, and financial regulators have taken note. Reports from the Financial Stability Board, BIS, IMF, and national regulators echo the same concerns: operational opacity, reserve quality, redemption risk, and the potential for large-scale dislocations in funding markets. Legislation is being drafted. Hearings are being held. Regulatory clarity is coming.

But clarity, if focused on the wrong dimensions, can still fail.

Most current proposals aim to turn stablecoin issuers into quasi-banks:

Requiring capital buffers,

Mandating real-time reserve transparency,

Enforcing redemption rights,

Restricting the types of assets held in reserve,

Imposing liquidity thresholds and stress-testing obligations.

These are all technically sound responses—and in a sense, overdue. But they share a dangerous assumption: that stablecoins are here to stay, and that the goal is merely to make them safer. They aim to domesticate the token, not replace the flawed design.

Yet the underlying flaw is not regulatory—it is architectural.

Stablecoins, even when regulated, remain detached instruments. They do not express economic intent, they do not bind parties together, and they do not emerge from the act of value creation. A better-regulated stablecoin may fail less catastrophically, but it still channels capital into economic vacuums unless tethered to real-world transactions.

More concerningly, regulation may legitimize the illusion: a government-blessed stablecoin becomes a token with an implicit guarantee—trusted not because it reflects anything real, but because it’s regulated. This mirrors the pre-2008 dynamic of AAA-rated synthetic CDOs: well-engineered, compliant, and utterly disconnected from underlying risk.

In attempting to regulate the surface, policymakers may end up cementing the deeper problem: a monetary instrument unmoored from context and permissive of systemic leverage.

Instead, the regulatory lens needs to widen. The question is not how to make stablecoins safer, but how to ensure that digital money only exists in verifiable economic relationships. That means moving away from free-floating bearer tokens and toward transaction-tethered claims issued by known and regulated agents—banks, businesses, or individuals—under shared digital trust protocols.

The Internet Trust Layer (ITL) offers precisely this: a decentralized architecture where financial instruments emerge only from agreed interaction, not speculation. Regulation can complement such models—not by dictating how money moves—but by defining who may issue it, under what rules, and with what auditability.

This is how financial stability is achieved—not by wrapping systemic abstractions in regulatory comfort, but by reconnecting digital money to the contracts, identities, and obligations that make up the real economy.

7. From Tokens to Transactions

Stablecoins were born out of necessity: a workaround for moving value in systems that lacked access to traditional banking infrastructure. They promised a digital equivalent of cash—fast, programmable, borderless, and unburdened by institutional gatekeeping. But in delivering that promise, they also delivered something else: an uncontracted, unaccountable form of money that scaled faster than trust could follow.

We now face a decision point. Stablecoins are no longer niche. They are embedded in trading systems, DeFi protocols, remittance rails, and increasingly even mainstream financial products. Their risk is not just theoretical—it is latent, invisible during periods of growth, and explosive during collapse.

The answer is not better tokens. It is a return to the principle that money is a consequence of trust, not a substitute for it.

That means shifting from tokens to transactions.

It means accepting that not all financial instruments should be fungible. Some should be traceable to the contract that created them, limited in their scope, and anchored in mutual obligation. Money should not just be redeemable; it should be understandable—who created it, for what purpose, and with what conditions.

The Internet Trust Layer embodies this principle. In an ITL-based financial system:

There are no floating tokens. Only claims between agents.

Each monetary issuance is tied to a contract and bounded in scope.

Value is verifiable, not just transferrable.

Trust arises not from the branding of an issuer, but from the proof of a relationship.

This may seem slower, more constrained. Maybe it is. But it is also more stable, more resilient, and more faithful to the purpose of money: to facilitate trusted interaction—not enable frictionless speculation.

As we watch the global financial system digitize at accelerating speed, we should not be seduced by the elegance of stable tokens. We should be focused on building stable transactions. Because when the next liquidity crisis unfolds, it will not matter whether your money is pegged to a dollar if the system it moves through is collapsing beneath it.

True monetary stability does not come from designating something “stable.” It comes from grounding money in the context of real economic life.

Tokens pretend. Transactions prove.

The future will belong to the networks that understand the difference.

Share this post