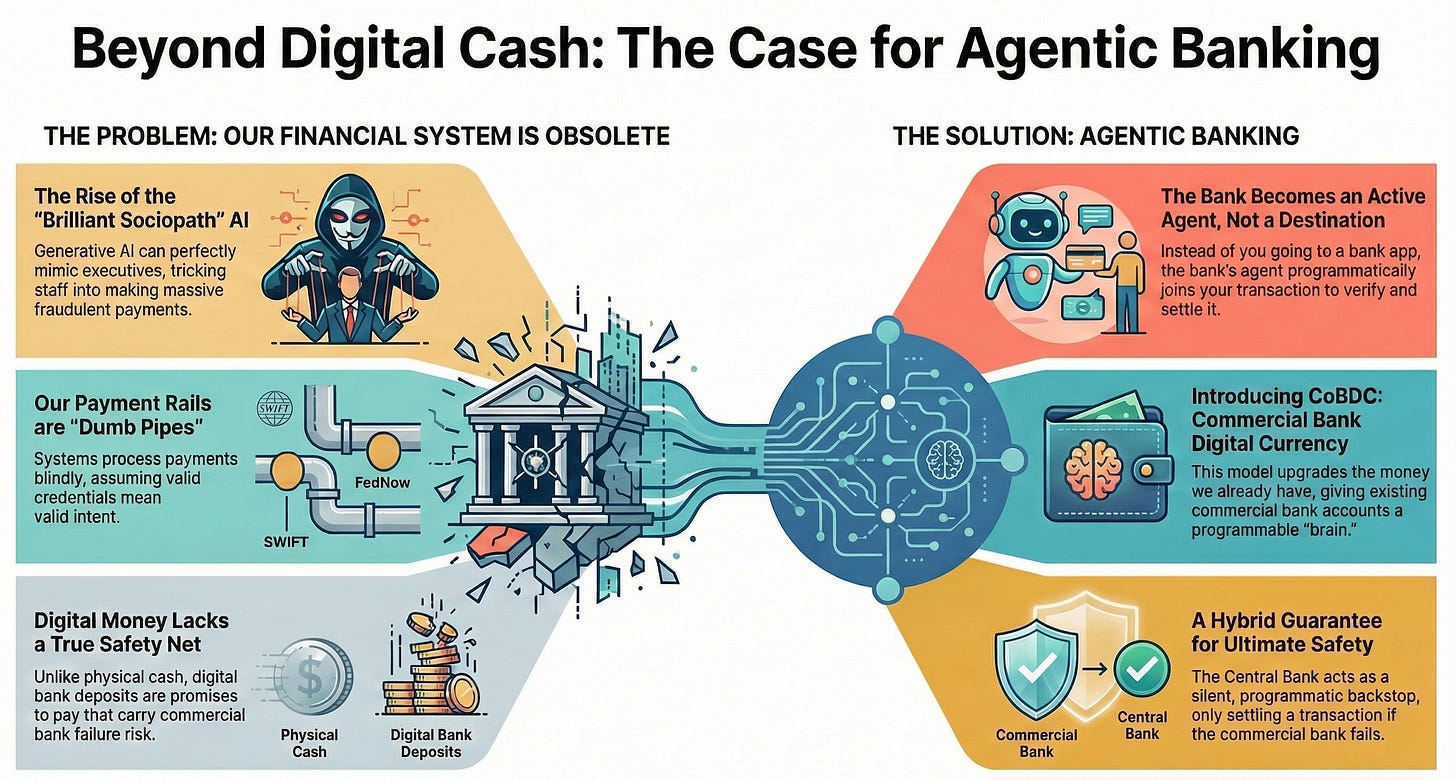

1. The Ghost of Cash and the Persistence of Risk

For the last five years, my physical wallet has devolved into a skeuomorphic relic, serving as little more than a graveyard for paper receipts I will never read and plastic cards that are slowly migrating into the secure enclaves of my phone. I simply do not use cash. The sheer friction of managing physical atoms cannot compete with the velocity and precision of digital bits. The efficiency of digital payments has rendered the act of handing over banknotes obsolete for my daily life, and frankly, for the vast majority of the modern economy. Every transaction I participate in—whether purchasing groceries, paying a consultant, or settling a monthly utility bill—is fundamentally legitimate. I have no need for the opacity or anonymity that physical bearer instruments provide, nor do I fear the digital audit trail left by my spending. The romance of the banknote has faded, replaced entirely by the utility of the ledger.

However, we must acknowledge that the gradual extinction of physical cash leaves a dangerous vacuum in the fundamental architecture of financial trust. We are trading a public utility for private conveniences, often without understanding the structural trade-offs. Central bank money has existed for centuries to serve a specific, non-negotiable function: it is the economy’s only truly risk-free asset. When you hold a physical banknote, you hold a direct liability of the state. It is money that does not vanish if a commercial bank becomes insolvent. In contrast, the money we see in our banking apps is merely a commercial bank’s promise to pay. It carries counterparty risk. If the bank fails, that number on the screen becomes a claim in bankruptcy court rather than liquid purchasing power. This quality of being “risk-free” is the bedrock upon which the entire credit-based commercial money system stands. Citizens, quite reasonably, demand access to an asset that is immune to the fragility of private institutions.

The current global debate around Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) muddies these waters by conflating the medium with the mandate. Technologists and regulators alike are trapped in a category error. They look at the physical banknote and try to emulate its physics—creating digital tokens or “digital cash” that function as bearer instruments. This approach misses the point entirely. We do not necessarily need a digital equivalent of the physical banknote to maintain safety. In fact, porting the anonymity of cash into the digital realm creates massive compliance risks, while porting the direct liability model via a Retail CBDC may create a surveillance panopticon where the central bank has a relatively easily activated opportunity to see every coffee you buy.

The solution requires more nuance. We need a mechanism that preserves the guarantee of the central bank, or other suitable guarantor—the “safe asset” property—without forcing the central bank to become the retail accountant for every citizen. The challenge we face is not merely digitizing cash; it is digitizing the safety net that cash once provided. We must find a way to decouple the liability from the ledger, ensuring that the concept of risk-free money survives the transition to a fully digital, agent-driven economy without dismantling the two-tier banking system that powers global credit.

2. The AI Threat: Why We Need Verified Rails, Not Just Faster Ones

While central bankers debate the metaphysics of digital cash, a much more practical fire is burning in the real economy. The need for new payment rails is not being driven by a desire for faster settlement—most domestic payments are already instant enough for human needs. The urgency is being driven by the collapse of identity assurance in the age of Artificial Intelligence. We are entering an era where the “who” in a transaction is becoming dangerously fluid.

We are witnessing the rise of the “Brilliant Sociopath.” Generative AI models have evolved to the point where they can mimic human communication with terrifying fidelity but operate without any concept of truth, liability, or conscience. The recent case, where a finance worker was tricked into transferring millions by a deepfake video conference of his CFO and colleagues, is not an anomaly; it is a preview of the new normal. In that meeting, the eyes, voices, and mannerisms were perfect. The only thing missing was the reality. The payment rails, dutifully blind to this deception, settled the transaction because the authorization codes were technically correct.

This exposes the fatal flaw in our current financial infrastructure. We have spent decades optimizing our payment rails to be “dumb pipes”—neutral, high-speed messaging systems that move value from Point A to Point B without asking questions. SWIFT, SEPA, and FedNow are designed to process instructions, not to verify intent. They assume that if the payer’s credentials are valid, the transaction is legitimate. This assumption works in a world where identity is hard to fake. It fails catastrophically in a world where a teenager with a laptop can clone a CEO’s voice or generate a perfect invoice from a non-existent vendor.

The industry’s response has been to add more friction—more passwords, more 2FA codes, more biometric checks. But this is a losing battle. Biometrics authenticate the biological user, but they cannot verify the context of the request. A retinal scan proves it is my eye looking at the screen; it does not prove that the “bank manager” I am talking to isn’t a synthetic puppet.

We do not need faster pipes; we need smarter payloads. We need to transition from “digital payments” to “digitally signed, verifiable transactions.” A true digital rail must carry more than just value; it must carry the cryptographic proof of the of the legitimacy of the agreement that triggered the movement of that value. It must be capable of verifying that the “CFO” authorizing the transfer is not just a video pixels, but a digital agent holding a valid, unforgeable credential signed by the corporation’s root authority. In this new architecture, the money itself becomes context-aware. It refuses to move unless the digital signatures on the contract, the identity of the participants, and the logic of the deal all align mathematically. The transaction isn’t just a settlement of funds; it is the settlement of a verified truth.

3. Agentic Banking: Don’t Go to the Bank, Let the Bank Come to You

The necessity for verified transaction contexts is being accelerated by a second, equally disruptive force: the arrival of “Agentic Everything.” We are rapidly moving beyond the era of passive chatbots that summarize emails and into the era of Agentic AI—software that actively plans, negotiates, and executes tasks on our behalf. In the very near future, you will not log into a travel site to book a flight; your personal AI agent will negotiate directly with the airline’s agent. You will not manually reorder inventory for your factory; the machine’s agent will negotiate the purchase order with the supplier’s agent. The economy is shifting from human-speed interactions to machine-speed negotiations.

This shift reveals a glaring obsolescence in our current banking model. Today, banking is architected as a “destination.” To settle a transaction, you must leave the context of the business deal and go to the bank—whether physically to a branch or digitally to an app. You are forced to act as a manual bridge, copying payment details from an invoice and pasting them into a banking interface. This model works for humans (albeit with friction), but it is fundamentally broken for agents. An AI agent cannot “log in” to a banking app, navigate a GUI, and look at FaceID. It needs a programmatic, deterministic way to settle the deals it negotiates without human hand-holding.

The fintech industry’s current answer is to give these agents “wallets”—dumb buckets of pre-funded value. But this is a security nightmare. Giving an AI agent a crypto-wallet or an open API key is like giving an intern the company credit card and hoping for the best. It creates a binary risk: either the agent has the keys to the kingdom, or it has nothing. If the agent hallucinates or is tricked by a “prompt injection” attack, the funds are gone. This is not a viable foundation for a serious automated economy.

We need to invert the architectural model. In an agentic economy, you should not go to the bank to settle a transaction. The bank’s agent should come to the transaction to settle it, after verifying that the transaction is, by their standards, a legitimate one.

This is the core principle of Agentic Banking. In this model, the bank is no longer a passive vault but an active participant—a “Sub-Contract Agent.” When I (or my AI agent) negotiate a business deal, I do not send money. Instead, I authorize my bank’s agent to enter the “Digital Meeting Room” (the transaction context) where the deal is taking place. My bank’s agent acts as a silent, verifying partner. It checks my balance, verifies my intent and the context, and places a “soft lock” on the required funds within my existing commercial bank account.

Crucially, the bank’s agent does not release the funds based on a blind instruction. It releases the funds conditional to the finalization of the business transaction. It observes the contract logic. Only when the “Digital Meeting Room” cryptographically confirms that the supplier has delivered the goods (or the airline has issued the ticket) does the bank’s agent execute the settlement. The transaction is the settlement.

This approach—what I call the CoBDC (Commercial Bank Digital Currency) model—allows us to upgrade the money we already have. We do not need to move our deposits into volatile crypto-tokens or government-run retail accounts to achieve digital speed. We simply need to give our existing commercial bank accounts a “brain.” By turning the bank into an active agent that can be invited into transaction contexts, we solve the friction of the agentic economy without sacrificing the regulatory safety and credit mechanisms of the traditional banking system.

4. The Hybrid Guarantee: Commercial Rails with a Central Safety Net

This brings us to the final structural challenge: restoring the “risk-free” quality of sovereign money without destroying the commercial banking sector. The widespread proposal for a Retail CBDC—where every citizen holds an account directly with the central bank—solves the safety problem by creating a catastrophic new one. It essentially nationalizes the retail payments interface, forcing the central bank to manage customer support, data privacy, and dispute resolution for millions of citizens. It also drains the deposit base from commercial banks, crippling their ability to issue credit and stifling the “risk pricing” engine of the economy. We should not burn down the factory to save the furniture.

I propose an alternative architecture, one that leverages the concept of the Internet Trust Layer (ITL) to create a hybrid guarantee. In this model, all digital money remains commercial bank money. The user continues to bank with Chase, Barclays, or Nordea. The primary settlement rail remains the CoBDC agent described above. However, we can programmatically embed the safety of the state directly into the transaction logic.

In the ITL, the “Digital Meeting Room” (the Context Agent) is sovereign over the deal. It holds the power to enforce the rules agreed upon by the participants. We can simply write a constitutive rule into the settlement logic: If the commercial bank’s agent fails to settle due to insolvency or technical default, the Central Bank’s, or some other suitable guaranteeing entity’s, agent is automatically invoked to guarantee the settlement up to the statutory limit in real time.

This turns the central bank, or another guaranteeing entity, into a silent, programmatic backstop rather than a retail competitor. The Guarantor Agent does not need to hold my account or track my coffee purchases. It only needs to be a participant in the network, ready to step in if, and only if, the primary commercial rail fails. The “Context Agent” acts as the neutral arbiter. It attempts to settle via the commercial bank first. If that fails, it presents the cryptographic proof of the failure to the Guarantor Agent, which then issues the settlement funds to the recipient.

To the user, the experience is seamless. They transact with the confidence that their money is safe, backed by the full faith and credit of the state, up to the approved limit. To the commercial bank, the deposit base remains intact, allowing them to continue lending and fueling the economy. To the guarantor, the operational burden is near zero; they only act in the rare exception of a bank failure.

This hybrid model renders the debate between “Private Stablecoins” and “Public CBDCs” obsolete. We do not need to choose between safety and innovation. By using agentic context to bind the two tiers of the banking system together, we create a form of money that is truly digital, fully private, and mathematically guaranteed. We effectively upgrade the existing deposit insurance scheme from a slow, bureaucratic legal process into a real-time, executable software function.

5. Conclusion: Designing the Digital Safety Net

We are standing at a crossroads in the history of money. The path of least resistance is to simply pave the old cow paths—making existing payments slightly faster, slightly cheaper, and slightly more mobile. But this incrementalism ignores the tectonic shifts occurring in the foundation of our digital society. The twin forces of Agentic AI and systemic fraud are rendering our current identity-blind, wallet-based infrastructure obsolete.

The alternative path—the path of the Retail CBDC—offers some safety but at the cost of privacy and the potential distortion of the credit economy. It is a centralization trap, attempting to run a 21st-century economy with the architecture of a command-and-control mainframe.

The third path, the one advocated here, is the path of Agentic Banking. By building an Internet Trust Layer, or an “Interbank Agent Network”, which technically speaking is the same thing, where banks act as agents and transactions occur in verified contexts, we can solve the paradox of digital money. We can have the speed of a digital token without the casino risks of crypto. We can have the “safe asset” guarantee of the guaranteeing institution without the risk of surveillance of the state. We can have an automated economy where AI agents negotiate and settle deals, but where “Brilliant Sociopaths” are checked by cryptographic laws they cannot break.

This future does not require us to invent new forms, or creation mechanisms, of money. It requires us to build new forms of trust. It invites us to stop treating money as a digital object to be hoarded in a wallet, and start treating it as a relationship to be managed by an agent. When we do that, we finally bridge the gap between the “Factory” of the real economy and the “Code” of the digital world. The future of money is not a new coin; it is a signed, verified, and guaranteed conversation.